- April 1, 2019

- Posted by: admin

- Category: advance

ABSTRACT

This study is an analysis of the worldview allegiance after the conversion of overseas Chinese in regard to ancestor worship. Ancestor worship has been a major obstacle to the evangelization of overseas Chinese in Malaysia.

Though the Western Church does not believe in ancestor worship; there has been—and continues to be—a discussion in the veneration of saints. The Protestant argument is that saints should not be involved or prayed to. However, they should be remembered for their exemplary lifestyle to serve as an inspiration for other believers. Thus, whatever is being said about ancestor worship would invite a discussion on SAINTS.

My research has shown that while it is an impediment at first, at post-conversion, overseas Chinese in Malaysia are not battling with the issue of ancestor worship as much as conveyed in literature. However, in their religious life, they consider God as the highest god (ancestor) and still tend to receive the blessing of God through the faithfulness of their religious life. Therefore, I claim that overseas Chinese in Malaysia have both continuity and discontinuity of worldview allegiance regarding ancestor worship.

KEYWORDS

Worldview allegiance, Overseas Chinese, Invocation of the Saints, Contextualization, Self-theologizing

I have worked for the evangelism of Chinese in China, Hong Kong, and Malaysia for over fifteen years as a missionary. During my study in Hong Kong as a seminarian, I met my wife who has a Chinese background from Malaysia. Her family was the fifth generation of a Chinese immigrant.

Ancestor worship has historically been very important in the culture and customs of Chinese society, regardless of its temporal and geographical boundaries. It continues to play an important role in the lives of many Asians, South Americans, and Africans, including those who have embraced the Christian faith. Western scholars and missionaries define ancestor worship as irrational, unscientific, and preliterate, but most of the Third World still believe in the power of their ancestors as a component of family unity. Therefore, ancestor worship is one of the most difficult obstacles to convert its believers to Christianity, especially for the Chinese who live in Malaysia. Ancestor worship is a cosmopolitan phenomenon that causes the controversy of the church not only in Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asian countries, but even in African countries. In Malaysia, it gives the socio-cultural identity of the Chinese in the multi-cultural (Malay, Chinese, Indian, etc.) relationship. In Hong Kong, people see ancestor worship as a cultural tradition associated with filial piety, rather than religious ones, due to secularization. In Korea ancestor worship is strictly more influenced by Confucianism. In Africa, people believe that an ancestor, as a god, is a direct influence on the lives of the living. Ancestors are therefore part of their lives.

There were different opinions on this issue, depending on different denominations, cultures and nationalities. Christian leaders claiming accommodation have argued that the social and ethical dimensions of consciousness can be separated from the religious meaning of ancestor worship. On the other hand, some say that ancestor worship should be viewed as a whole, and social, ethical, and cultural motives inherent in consciousness cannot be separated from religious elements. Therefore, I prefer the term ancestor worship rather than ancestor veneration or respect.

OVERSEAS CHINESE

In general, Overseas Chinese refers to people who were born in China and settled in other countries and live in another country. The Chinese community, like the dispersion of the Jews in the first century of the Christian era, is a group of people who are scattered widely in Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the United States, and so on, all while maintaining their Chinese identity.

Wherever they live, they tend to form communities with their strong identities. With their passion for diligence and wealth, they are doing their best in business and study, and are forming a higher level in each society. Overseas Chinese are also very superstitious and tend to visit fortune tellers about important issues: business, health, education and so on. Overseas Chinese serve various gods and spirits like the heavenly gods, house gods, god of land, ancestral gods, etc. They believe that these gods are Chinese gods and that they should serve them. On the contrary, Christianity is understood as a foreign religion against such gods, especially ancestral gods.

INVOCATION OF THE SAINTS

The Invocation of the Saints is a doctrine held by the Roman Catholic Churches and Orthodox Churches. Anglican churches also follow the Catholic’s understanding of invocation of the Saint in a lesser manner. Percival claims that “the Anglican Church does not condemn, but is silent with regard to, the practice.” Origen is believed to be the first person to discover the invocation of the saints. According to Eusebius, after the first generation of Christianity had passed away, the wrong doctrine came to the Church, and the seeds of prayer for the saints began to be sown around AD 240. He writes, In Cantica, Homily 3:

If all the saints who have departed this life and still retain their love for those who are in the world are said to be concerned for their salvation and to aid them by their prayers and by intervention with God, this will not be unfitting.

The “Communion of Saints” is one of the articles of Christian faith as stated in the Apostles’ Creed, saying that “I believe in the communion of saints.” The Greek word for “communion” (Koinoia) is a common word in the New Testament, occurring nineteen times. It implies “fellowship, participation, contribution.” The phrase “Communion of the saints” appears in the Apostle’ Creed, which is missing in the New Testament and Christian writings of early apostolic times. The practice of praying to the saints has been found in Christian books since the third century. Tertullian, in his Apology, said that a member of the church who sins seriously against brothers cannot attend the fellowship of the saints. In Catholicism, the church is defined as a fellowship between the living—those who are still on earth—and the living dead—those who are in purgatory and in heaven. Therefore, Catholics argue that the communion of Saint should include ancestors.

There is no doubt that the historical record of the origin of invocation of the saints has been mixed with the ancient documents of the Gentiles. According to Ludovicus Vives, in a commentary on Augustine’s De Civitate Dei (City of God), there is no difference between pagan idolatry and invocation of the saints except in the names and the terminology.

Many pagans thought that the supreme god was too sublime to take care of people’s personal affairs or to be approached by them. Therefore, the lower gods were easier for people to approach and could also be influenced by human affairs because these low gods had some authority similar to the highest god. They could bring what people wanted. As a result, a great variety of gods were invented—heavenly gods, earthly gods, gods of the sea, gods of woods and gods of house, and others.

Plato’s followers set up two kinds of mediators between God and man. These mediators are demons and the souls of the dead. Augustine explains that in De Civitate Dei Plato’s followers assign the highest place to God, the lowest to man, and the intermediate place to the demons. Demons enjoy various sacred ceremonies, rejoicing in respect, gift, and honor. They are angry if anything is neglected. They act as intermediaries between gods and people. They are thought to have come from the souls of the dead. Regarding this matter, the teaching of the Catholics about mediations, intercessions, protections, merits, and aid of the saints is totally agreeable with these opinions of the Platonists, only the name being changed.

The Catholic doctrine of invocation was confirmed at the Council of Trent under the supervision of Pope IV in 1563. The invocation of the saints evolved into Mariology. Catholics believe that Jesus Christ is truly a mediator of God’s grace, but he is an angry judge who needs to be placated. Mary can intercede for sinners before her son, because she is the perfect mother and Jesus could never turn down her intercessions. So Catholicism claims that Mary was conceived without original sin (Immaculate Conception of Mary), was an ever-virgin (Perpetual Virginity of Mary), was taken directly to heaven at the end of her life (Bodily Assumption of Mary before the death), and can appear to people and gives messages to them (Apparition of Mary). Mary is also the mother of God, the Mediatrix of Graces, Co-Redemptrix, Mother of the Church, Queen of Mercy, and Queen of Heaven. The Vatican II documents reaffirm Mary’s role in Marian doctrine and salvation.

Thus, because Catholics have the veneration of the saints they teach that the Chinese practicing ancestor worship keeps Christian value, and is not wrong at all. In fact, once a year in Malaysia, ancestor worship is being offered at church, and there is no difficulty for Chinese to accept Catholicism.

CHINESE RELIGIONS AND ANCESTOR WORSHIP

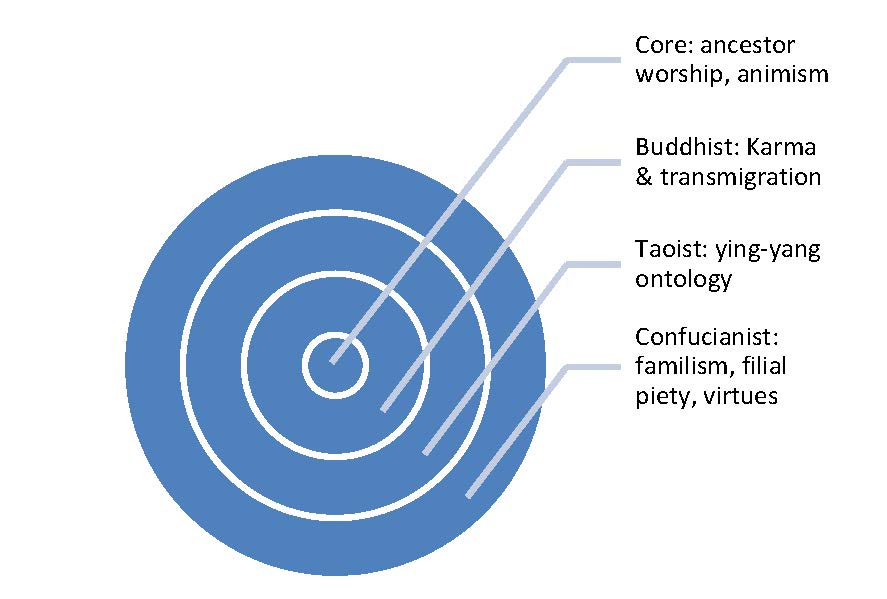

When people ask Chinese people about their religion, many Chinese think that it is hard to answer because their religion is a synthesis of separate elements: Chinese folk religion (traditional religion), Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism (Daoism). As you can see in Table 1, the core of these religions is ancestor worship.

The Chinese believe that after death the soul is not extinguished but transformed into the spirit of the ancestor. Ancestral soul refers to the dead soul of kin, national hero, and leaders. Their belief in the ancestral soul is based on the belief on the immortality of the human soul and the life after death. Ancestral spirits are interested in what happens in the home. So they sometimes return to their families and eat their meals symbolically. They can appear in dreams and fantasies. They also help the family especially when it is good and bad. Therefore, Chinese people worship them.

Table 1. The Syncretistic Multi-layer of Chinese Folk Religion

CRITICAL CONTEXTUALIZATION AND SELF-THEOLOGIZING

David Bosch emphasizes the meta-theology and argues that the situational nature of all theology requires a universal and transcendent dimension of theology. In order to avoid syncretism in mission, Paul Hiebert presented four stages of critical contextualization. It is “phenomenological analysis”, “ontological critique”, “evaluative response”, and “transformative ministries”. He asserts that the church in particular serves as a hermeneutic community.

After missionaries have established local churches, local theologies encounter questions about how the gospel relates to local traditions. So how can local theologies preserve the prophetic message while expressing the gospel? Also, how should the missionaries respond when local church leaders develop local theologies that they claim are more relevant to their culture? This is the issue of “self-theologizing” by local Christians according to Paul Hiebert.

For many years, missionaries and Christians in Asia have debated about the appropriate Christian response to ancestor worship. Roman Catholics settled over the issue in Rites Controversy, while Protestant Christians continually have been debating until now. The historical perspective of ancestor worship in China has shown different approaches between the Jesuits and Franciscans/Dominicans within the Roman Catholic Church. The Catholic Church finally ended a long time struggle by accommodating ancestor worship. In 1936 Pope Pius XII officially ended the controversy by officially allowing ancestor worship to be a Chinese culture for the filial piety. The Protestant Church, on the other hand, has been struggling in answering this fundamental problem up to the present time. William Martin, a 19th century Chinese Protestant missionary who ministered to the intellectuals, emphasized the method of accommodation and Henry Blodget, who ministered to the public, said that ancestor worship is inherently idol worship which cannot be cured. In this context, the Asia Theological Association and the Taiwan Church Renewal Center co-sponsored the “Consultation on Christian Response to Ancestor Practices”.

According to Henry N. Smith, there are four models of strategic encounter: displacement, substitution, fulfillment, and accommodation. The first model is a displacement model. This theory judges every aspect of ancestor worship to be thoroughly idolatrous. Therefore, ancestor worship is no revelation from God worth preserving. The second model is a substitution model. It recommends functional substitutes, which are intended to replace the social functions of ancestor worship. For example, a family Bible with the names of ancestors written in the blank pages could be set on the altar where tablets used to rest. A third model is a fulfillment model that introduces Christianity through the religious and social values of ancestor worship. The fourth model is an accommodation model. The beliefs, rituals, and social functions associated with ancestry are somewhat consistent with Christian beliefs and practices.

How should we deal with beliefs and practices related to ancestor worship? There are two parts to this question: (1) How should Christians relate to biological ancestors who gave them their body and cultural life? (2) How should they deal with spiritual ancestors, those who have passed their faith to them?

First, it relates to biological ancestors. Practices such as burning spirit money, offering incense, holding joss sticks, and bowing before the deceased are unscriptural and should be discarded. The incense was always used when communicating with the gods or worshipping the dead. On the other hand, Christians must find ways to love and respect their parents and family by participating in the non-religious part of the funeral. They should attend non-Christian relatives’ funerals, talk about the deceased, listen to family members, and help them prepare as their conscience permits. Some Korean Christians offer Christian memorial service on the anniversaries of the death of a relative. The focus is to worship God and thank God for the life of the ancestors.

Second, it deals with spiritual ancestors. The Bible speaks of spiritual ancestors (Hebrews 12: 1) and fellowship of saints. Christians often do not see the heroes of faith as an example of their lives and do not introduce spiritual ancestors to their children. We must remember, appreciate and imitate the faith and exemplary life of spiritual ancestors of faith. However, the question of spiritual ancestors raises difficult questions in some parts of the world. Some African theologians argue that Christ can be portrayed as an ancestor, or a departed elder, because he stands as the intermediary between God and humanity. In Malaysia, one of theologians whom I conducted an interview with insists that God is our great-great ancestor. He claims that we can view God as the first ancestor. Here again, a careful reflection is needed to develop a theology of spiritual ancestors.

MISSIOLOGICAL FINDINGS AND IMPLICATIONS

Previous studies of scholars have reported that Chinese in Malaysia maintain a “loyalty” with little change in worldview before and after conversion to Christianity. However, according to my findings, they show a changed view of the world in several ways. The major changes are as follows.

First, it is discontinuity of the existing worldview. The issue of ancestor worship among converted overseas Chinese is no longer a chief problem in their religious life. Also, they have a positive attitude towards death. Before the conversion to Christianity, most of them confessed a fear, fear of life, and fear of the afterlife. They admitted that they no longer had fear of death and enjoyed peace in their hearts. This is a fundamental difference from previous religions and current religions (Christianity). Therefore, Christianity gives a clear answer to the question of the future.

Second, it is continuity of the existing worldview. In the part of religious life, Chinese in Malaysia still try to receive the blessings of God through faithful religious life by considering God as the highest ancestor in the way of worshiping the ancestral gods that they believed before. The Pentecostal movement in Malaysia offers an indigenization of Christianity, with individual focus on spiritual strength. For Chinese, experiencing the fullness of the Holy Spirit not only symbolizes unity with spiritual powers, but also acquires spiritual power to solve problems in daily life. They believe that spiritual power can control all aspects of their lives. They also believe that prayer and exorcism are complementary to medical treatment.

Third, the image of Christians and Christianity has an absolute impact on the conversion of Chinese. Many have confessed that they become Christians because of the love of Christians and the religious activities in the church. Friendship evangelism is a very effective tool that brings Chinese to the Lord. Christians should become a model of life for people.

SUMMARY

The issue of ancestor worship is a global phenomenon and an obstacle to the evangelization of Asia. Methods to overcome this have been studied for a long time. Catholics emphasize the cultural aspects of ancestor worship with accommodation strategies and teach that Christians should actively participate. Protestantism does not yet have a unified solution, but there is an opinion that local leaders analyze the situation on the basis of the Bible and “Christian theology” and then an alternative should be proposed. In order to understand ancestor worship in Asia, I have studied the invocation of the saints and veneration of Mary in the West. Saints should not be involved or prayed to. However, they should be remembered for their exemplary lifestyle to serve as an inspiration for other believers. While ancestor worship is an impediment at first, at post-conversion of overseas Chinese in Malaysia are not battling with the issue of ancestor worship. However, there is a tendency to deal with God in the old way of religion, a reluctant form of faith, when living a faith life after conversion. Therefore, it can be said that the overseas Chinese in Malaysia have a pattern of discontinuity of worldview and a continuity of worldview on ancestor worship.

REFERENCES

Abbott, Walter M., and Council Vatican. The Documents of Vatican II. New York: Guild Press, 1966.

Agassi, Joseph and I. C. Jarvie. Hong Kong: A Society in Transition A Study in Westernization. New York: Praeger, 1969.

Bae, Choon Sup, and Petrus Johannes Van der Merwe. “Ancestor Worship–Is It Biblical?” Hervormde teologiese studies 64, no. 3 (2008): 1299-1325.

Bosch, David Jacobus. Transforming Mission : Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission American Society of Missiology Series. No. 16. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1991.

Carpenter, Mary Yeo. “Familism and Ancestor Veneration: A Look at Chinese Funeral Rites.” MISSIOLOGY 24, no. 4 (1996): 503-517.

Chemnitz, Martin. Examination of the Council of Trent Chemnitz’s Works ; Vol.3. St. Louis, MO: Concordia Publication House, 2007.

Clarke, Ian. “Ancestor Worship and Identity: Ritual, Interpretation, and Social Normalization in the Malaysian Chinese Community.” Sojourn 15, no. 2 (2000): 273-295.

Corduan, Winfried. Neighboring Faiths: A Christian Introduction to World Religions. Downers Grove, IL.: InterVarsity Press, 1998.

Haines, J. Harry. Chinese of the Diaspora. London: Published for the World Council of Churches, Commission on World Mission and Evangelism, by Edinburgh House Press, 1965.

Hiebert, Paul G. Anthropological Insights for Missionaries. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Book House, 1985.

Hiebert, Paul G., R. Daniel Shaw, and Tite Tienou. Understanding Folk Religion : A Christian Response to Popular Beliefs and Practices. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Books, 1999.

Jahn, Curtis A. . A Lutheran Looks At… Catholics. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Northwestern Publishing House, 2014.

Janelli, Roger L., and Dawnhee Yim Janelli. Ancestor Worship and Korean Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1982.

Jebadu, Alexander. “Ancestral Veneration and the Possiblity of Its Incorporation into the Christian Faith.” Exchange 36, no. 3 (2007): 246-280.

Jordan, David K. “The Glyphomancy Factor: Observations on Chinese Conversion.” In Conversion to Christianity: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives on a Great Transformation, edited by Robert W. Hefner. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. A History of Christian Missions in China. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1929.

Liguori, Alfonso Maria de’ Saint Dollen Charles. The Glories of Mary. Staten Island, N.Y.: Alba House, 1990.

Lowe, Chuck. Honoring God and Family: A Christian Response to Idol Food in Chinese Popular Religion. Wheaton, IL: Bangalore, India Evangelical Missions Information Service; Theological Book Trust, 2001.

Neill, Stephen. A History of Christian Missions. London: Penguin Books, 1964.

Percival, Henry R. The Invocation of Saints Treated Theologically and Historically. London: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1896.

Ro, Bong Rin. Christian Alternatives to Ancestor Practices = [Zu Xian Chong Bai Wen Ti] Asian Evangelical Theological Library. Taichung, Taiwan, ROC: Asia Theological Association, 1985.

Smith, H. N. “Christianity and Ancestor Practices in Hong Kong: Toward a Contextual Strategy.” Missiology: An International Review 17, no. 1 (1989): 27-38.

_________. “A Typology of Christian Responses to Chinese Ancestor Worship.” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 26, no. 4 (1989): 628-647.

Stark, Rodney. The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries. New York: HaperOne, 1996.

Swete, Henry Barclay. The Holy Catholic Church: The Communion of Saints; a Study in the Apostles’ Creed. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1915.

Tan, Kim Sai. “Christian Alternatives to Ancestor Worship in Malaysia.” In Christian Alternatives to Ancestor Practices = [Zu Xian Chong Bai Wen Ti]edited by Bong Rin Ro, 332 pages. Taichung, Taiwan, ROC: Asia Theological Association, 1985.

Triebel, Johannes. “Living Together with the Ancestors: Ancestor Veneration in Africa as a Challenge for Missiology.” MISSIOLOGY 30, no. 2 (2002): 187-197.

Wan, Enoch Yee-nock. Christian Witness in Pluralistic Contexts in the 21st Century Evangelical Missiological Society Series ; No. 11. Pasadena, CA.: William Carey Library, 2004.

Wulfhorst, Ingo, Federation Lutheran World, Theology Department for, and Studies. Ancestors, Spirits and Healing in Africa and Asia: A Challenge to the Church. Geneva, Switzerland: Lutheran World Federation.

Jaewoo Jeong

jeongong@gmail.com

Dr. Daniel Jaewoo Jeong graduated from the University in Korea, and was involved in short term missions in China, India, and Bahrain. He joined WEC International to serve the Hui Muslim in China. He then moved to Malaysia and co-organized a Chinese training center to train and equip local people for the continual expansion of the Lord’s work. While in the US, he studied Intercultural Studies (M.A) at Fuller Theological Seminary in 2008 and Missiology (Ph.D) at Concordia Theological Seminary in 2017. Currently, he lives in Kota Kinabalu Malaysia, training future missionaries from Asia. He has a Malaysian wife (Chinese) and three kids—two daughters and a son.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Can I have a pdf copy of this article