- October 13, 2019

- Posted by: admin

- Category: advance

Worship in Asia should not be tied to assumptions and values, imposed from the outside. Rather Christian worship in Asia should utilize rituals intended to ensure meaningful worship empowered by the Holy Spirit who enables people to be who God created them to be in the pluralist contexts Asian Christians find themselves. Beyond worship, the principles presented here also pertain to developing biblical theologies that reflect local expressions of relevance—people living a full and meaningful life.

As an anthropologist interested in culture and the contexts that dictate human interaction with the whole of the environment, I am aware of the well-known anthropologist Clifford Geertz who did some very creative research here on the Island of Bali. Perhaps his best known article is an ethnographic description of a Balinese cockfight (Geertz 1972). Cockfights, it turns out, are the stuff of effective relationship in Bali—past, present and future, regardless of their being illegal. Far beyond training the cocks, gathering, and betting (the illegal part) Balinese people consider cockfighting part of their identity; men view the birds as an extension of themselves and their commitment to a community. Cockfighting, then, is a measure of what it means to be Balinese. The interpretation of these events is open to discussion and contained within the local expressions associated with cockfighting—that is to say dependent upon who is telling the story (Geertz 1973, 437).

Before Geertz there was Margaret Mead who focused on how the Balinese raised their children and committed to raising her own daughter within the constraints of Balinese expectations, at least while she was in that context (Mead and Heyman 1965; Bateson 1984). So what we learn from anthropologists is the need to take the local context seriously, learn from it, and understand the cultural circumstances—take note of how people live their lives.

In 1908, the Dutch arrived on the Island of Bali and quickly saw human expressions, including cock fights and child rearing, through their own eyes rather than making an effort to appreciate local culture. This was true of administrators and missionaries alike. Armed with their reformed theology and catechism, missionaries sought to ban all they deemed “pagan” and sought to civilize the Balinese in light of their well thought out theology; organized, structured, and defined by their reading of the Bible. Thus, the missionary approach to local culture and the anthropological approach were immediately contrastive and of no consequence to the other—a quest for knowledge on the one hand and a proclamation of knowledge and truth on the other (Hiebert 1999, xv).The results, however, had great impact on the people of Bali who were largely of Hindu background.

Into this epistemological debate Kosuke Koyama enters the discussion, not in Bali, but in Thailand where many of the same issues pertained, but in a Buddhist framework. Koyama arrived in Northern Thailand from Japan and viewed life through his Japanese eyes. As an Asian, he quickly realized that Thai people were concerned with the same things Japanese farmers also experienced; sticky-rice, peppers, dogs, cats, planting rice, fishing, bicycles, rainy season, even the lottery and stomach aches(Koyama 1999, xv). This was the stuff of being human and being Asian though each culture processed them differently. But the difference was not so great that he could easily dismiss it as Western missionaries once did. Koyama determined to preach about things people understood rather than to present theological premises that were beyond their comprehension. How could the Bible benefit the farmers and people of Northern Thailand as it benefited Koyama himself? Rather than “great thoughts” from theologians like Aquinas or Barth, Koyama tried to see the “face of God in the faces of the people”(Koyama 1999, xi).How could he bring biblical concerns and issues into the experience of those in his small congregation in the middle of the paddy fields?

Though a missionary, Koyama (like anthropologists) sought to learn the language and understand the context in which people lived their lives. Koyama considered it more important to prepare himself for presenting the gospel which he saw as the content of Scripture which in turn, he connected to the context in which people made sense of life. As Christ incarnated and spent thirty years preparing himself for ministry, and the Apostle Paul observed socio-religious behavior wherever he went and recognized an opportunity to present the “unknown” god to the Athenians, so Koyama strived not to replace ancient understanding with something new, but rather to speak of “mental enrichment” (Koyama 1999, xiii). Christianity should not “replace” Hinduism, Buddhism or Islam (or any other religious expression) but rather enhance and draw further attention to the “face of God” (Koyama 1999, xiii). This was Paul’s message as he emphasized the need to connect with all people so he could win as many as possible and in doing so considered himself the primary learner, sharing in the blessing—both recipients and presenters learn and God’s Kingdom is glorified (I Cor. 9:22, 23).

It is to this process of mutual learning while recognizing God’s presence is already there, that I turn in this presentation. Out of their circumstances people utilize ritual and ceremony to worship in ways unimaginable to outsiders but relevant to themselves, and acknowledged by God—a sweet smell that rises (Liv. 1:6, 13, 17; Phil 4:18). As a cognitive anthropologist interested in what people need to know in order to act appropriately within their context, I am interested in discovering the conceptual triggers that will enable people to respond to God appropriately—from their perspective. I am interested in seeing how the Holy Spirit will lead people to adjust their expressions and bring them into line with God’s intended purpose for them. As a missionary, I am interested in what I need to learn about a people’s expressions of worship that will enable me to recognize “the face of God” and approach people from below in order to present God’s view from above in the context of human life—incarnation. This is our God given task, may we learn from each other, avoid repeating past mistakes, and recognize God in every context.

THE NATURE OF PLURALISM

All who are engaged in the context of Asia must account for religious pluralism. This implies a variety of spiritual understanding and its application to interacting with spiritual powers, particularly the variety of ideas about deity, nirvana, spiritual presence in the world around us, and all the associated practices that enable people to navigate this complex spiritual environment. As a Bishop in the Church of South India, Leslie Newbigin experienced firsthand the nature of pluralism; cultural, linguistic, socio-political and spiritual. He recognized the need for the church to reflect the context in which it grew, citing five key principles that emerged from his observations: (1) ecclesial reality emerges from the local church;(2) this reality is displayed in the rural areas; (3)discipleship, witness and service grow out of a local congregation; (4) each congregation is shaped by its local environment; and (5) ministry training must be in the vernacular language (Newbigin 2009, 57ff). From this grew his famous dictum that the church serves as “God’s embassy in a specific place” (Newbigin 1989, 229). Therefore, by definition the church is a hermeneutic, an interpretation, of what it means to be Christian in a particular context. The church, then, is by definition missional, serving as Christ’s representative to the people who can observe incarnation and come to appreciate what it is like to have God with them. As John Flett notes, “the congregation assumes its necessary missionary form, finding its identity in the event of being gathered, in the event of fellowship with [its] neighbor”(Flett 2015, 213).

Newbigin learned all this in the context of South India. After 27 years in India, assuming pluralist issues and dealing with the complexities of transition from colonialism to independence, Newbigin returned to the UK where he observed the church in a state of breakdown where the culture was increasingly “secularized and skeptical, distrustful of religion and disillusioned with the church, searching for meaning but unsure where to find it” (Shenk 2015, 47). The answers came from Newbigin’s experience in Asia. For him, meaning and relevance for human beings came out of a relationship with God through Jesus Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit; Christian relevance is not a product of socio-religiosity but rather an interactive, biblically based relationship with a triune God as laid out in the Gospel of John. Newbigin’s message for a deteriorating Western Church—both in Europe and later, though no less pronounced, in North America, was to return to a relationship with God irrespective of the enlightenment and plausibility structures of so-called ‘Modernity’ which had led the church and the cultures that embraced it into a three hundred year dead end (Karkkainen and Karim 2015).

For Newbigin, then, pluralism, observed and distilled in an Asian, multi-religious environment, and applied to what he observed in the West, served as the means to move beyond culture, to a re-reading of the Bible which was also developed in a pluralist environment. For Newbigin, the Bible is a commentary on “cosmic history”, connecting the beginning to the end in order to reveal God’s expectation for the nations (political pluralism) which make up the human family in its particularity (read diversity or plurality) and its generality (read unity despite individualism). The Bible reflects on one nation “to be the bearer of the meaning of history for the sake of all, and of one man called to be the bearer of that meaning” (Newbigin 1989, 89). It is in the plurality reflected in the identity of a nation, and a person in relationship to the creator, sustainer, and completer of history, that contemporary culture, wherever it is found, makes sense.

This is why, as an anthropologist and a missionary, I focus first on the context of those with whom I wish to interact and eventually present a message. At the same time I seek to understand the biblical text in its context, desiring to find connections between God’s view and human views(Shaw 1989). When I find a match, I see that as the place to begin connecting humanity with divinity and then pray for the Holy Spirit to open people’s spiritual eyes to bring transformation to their context—a biblically driven transition that leads people to experience God with them. This leads me to a discussion of the nature of ritual which will ultimately lead to an appreciation of worship. In the process I will briefly develop some concepts from cognitive anthropology that help move us beyond earlier models of mission practice and encourage a new approach to communicating the gospel in ways that demonstrate relevance within the thought patterns unique to a particular context and thereby reduce misunderstandings that are often decried as leading to syncretism.

THE NATURE OF RITUAL

Despite anthropological interest in ritual from the beginnings of the discipline over 125 years ago, there remains little agreement on just what ritual and its close cousin, ceremony, really is. For the most part, anthropologists still describe what they see rather than define these often complex, symbolically rich, and spiritually intricate events. (Moro 2012).How people act out their beliefs and values through the rites that are familiar to them tell us much about their interaction with spiritual presence and its manifestations in their context. Edmond Leach, writing about the Kachinin northern Burma, notes that rituals are actions that communicate meanings or embody those meanings to reflect sacred or profane patterns that can be compared cross-culturally (Leach 1964). Later, David Hicks characterized ritual as “stereotyped, repetitive behavior or set of behaviors that uses symbols to communicate meaning” (Hicks 2010, 94).

More recently, cognitive anthropologists have recognized that aspects of religious thought and behavior are a natural part of the way the human mind works. If this is correct, it means that religious thought and behavior around the world is rooted in cognitive processes common to all human beings. For cognitive science of religion (CSR) purposes researchers define ritual very specifically as an observable action that someone performs on someone or something else that somehow involves the power or presence of a superhuman or supernatural being such as a god, spirit, or ancestor(Barrett 2011, 120). The effect of the ritual must be specifiable—the effect should be clearly describable, but it need not be directly observable. The ritual action and the ritual participants must be observable, but the effect need not be. Rituals could have positive consequences (as in blessings) or negative effects (curses), and need not be part of a formal religious system or setting (Barrett 2011, 119ff).

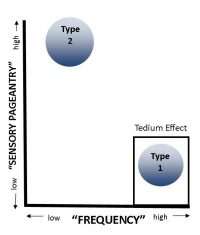

In general, most missionaries have not understood ritual other than to perceive it does not fit their categories for spiritual engagement and have, therefore, often banned it from Christian expression. Two cognitive psychologists, Robert McCauley and Thomas Lawson have developed a theory of “religious ritual competence” in which they hypothesize that interaction in the spiritual realm operates on the same set of categories and behavior patterns as activity in the physical realm. Furthermore, since human beings need assistance in their involvement with spiritual influences, human agents in the form of shamans, priests, prophets and teachers, understand superhuman agency, and assist people through ritual and ceremony. Based on this hypothesis, McCauley and Lawson have postulated two primary characteristics of ritual: “performance frequency” and “sensory pageantry” (2002, 6). Both aspects enhance memory which in turn impacts cultural transmission. These two dynamic properties are affected by what they call “culturally postulated superhuman agents” – gods and other culturally defined spiritual entities. These spiritual beings, in turn, interact with human religious practitioners who perform ritual on behalf of human patients (the recipients of spiritual action). Simply put, ritual involves observable, repetitive practices, often mediated by spiritual practitioners who connect spiritual beings with human beings.

FIGURE 1: The Nature of Ritual & Ceremony

(From McCauley & Lawson, 2002:51)

Figure 1 depicts two types of rituals; Type 1 based on frequency and Type 2 based on sensory pageantry. Because of frequency and lack of emotional impact, Type 1 (exemplified by communion, daily puja, or performing salat five times a day) is remembered by virtue of sheer repetition. Though memorable and easily reproducible, the net effect of such repetition is a high potential for what McCauley and Lawson call a “tedium effect” that often leads to indifference and boredom which precipitates nominalism. Thus, excessive repetition leads to a focus on the form rather than the intended meaning of repeated chants, mantras, recitations and liturgies common in religious experience (as illustrated on the lower right in Figure 1). By contrast, what they call “Type 2 rituals” are relatively infrequent but have high emotional impact on those involved due to the accompanying pageantry (events like initiation, weddings and funerals—what anthropologists typically call “rites of passage”).Specific episodes from life trigger “episodic memory”; making superhuman expressions relevant to the reality of living life provides the focus of faith(McCauley and Lawson 2002, 43, 87).

Ritual and ceremony can thus be aligned to enable worshipers to focus on God. The process for accomplishing that goal will be specific to each worshiping community. It may reflect frequent, more-or-less tedious repetition of ritual and ceremony (for example the stable structure of liturgy in Roman Catholicism or Anglicanism) or it may reflect “sensory pageantry” that is much more event specific and enhances memory through individual or collective experience (as less liturgical, Pentecostal, expressions that tend to emphasize ecstatic worship, speaking in unknown languages, and healing in the context of a service).Ideally, these should not be considered contrastive, but rather complimentary approaches to superhuman presence. When worship reflects the nature of obedience to God’s command as perceived by faithful communicants who are committed, loyal, and sincere, spirituality is dynamically engaged, whether frequent or highly emotional, patient or agent-focused.

To shift the focus to relevance, I cite two anthropological linguists, Daniel Sperber and Deirdre Wilson. They developed what they called “relevance theory” to explain how language is directed to communicate in ways that make sense to those who use and interact with it (Sperber and Wilson 1986). This sense making capability is reflected when communicators present their intent to share a message and those who hear respond based on an understanding of that intent. Communication needs to capture the conceptual awareness that begins with a communicator’s desire to pass on information, but it is simultaneously dependent on the knowledge-base of the audience it connects with. If the information is considered to be foreign and too difficult to understand, people will tend to ignore it and stick with their own ideas. How much energy people are willing to expend on processing information is largely a product of the perceived benefit. Changes come about from a desire to build relationship through the communication process. The greater the shared experience, the greater the likelihood of effective exchanges that will create mutual understanding and relationship. This is exactly what Koyama was doing when he used water buffalo illustrations out of Thai experience, rather than inflict systematic theology from Europe on Thai farmers.

Sperber and Wilson further emphasize that if the intent is sufficiently clear and people consider it important to use and make a difference in their lives, they will be willing to expend more energy to understand. Kraft had it right when he emphasized “receptor-oriented communication” (Kraft 1979, 394); (also Kraft 1983, 25, 1979). In mission theory we must move to a model that emphasizes the process rather than the product of communication. The Bible provides a wonderful example of God patiently striving to communicate the importance of relationship so human beings will interact directly with God which, in turn impacts their interaction with each other. God created Adam and Eve and then went to talk with them in the Garden. God communicated directly with Noah who, despite adversity and apparent inconsistency with reality (it had never rained before) took God at his word and saved humanity. God’s interaction with Abraham and his subsequent progeny demonstrate a lifetime of trust that resulted in the whole world being blessed (Gen 12:1-3, Gal. 3:6-9).We could go on and on—it is the story of the Bible, God makes his desire to be in relationship clear and human beings either accept or reject it. What is important here is appreciating how God’s intent becomes cognitively relevant to and understood by human beings.

According to relevance theory, communication is always designed to achieve balance (Sperber and Wilson 1986, 38).Both sides of the intent-inference equation are impacted. The mental-neurological network is always seeking balance, which, when achieved goes far beyond the impact of speech and includes all the senses, which are constantly enhancing human experience and triggering adjustments relevant to understanding (Hall 1959).Thus, both messengers and receptors are changed. Each arrives at a new balance that provides insight regarding the entire experience (Freire 2008).

That understanding is reflective of schema, another cognitive concept which describes how people develop and use ideas based on their experience in the physical and social environment around them (D’Andrade 1995, Strauss and Quinn 1997). People form these concepts through social and physical interaction and through internal reflection on their experience (West 2007, 33-34). Schemas, then, are the well of culturally and experientially developed resources from which every human draws when reflecting on and interacting with their world. Relevance theory explains how people use schemas within their cognitive environments to infer meaning from observed objects or events. The two cognitive concepts work closely together to inform what people think about and how to adjust communication to make an appropriate impact. John Medina stresses the importance of finding the “triggers” that suggest it is important for people to pay attention if they are going to make sense out of the incoming information—what do people need to know to understand a message? They always start with what they know and gradually, by extension of meaning, interpersonal relationship, and built up trust begin to see the relevance of something new to their circumstances (Medina 2014, 6, 7).

If, then, the intent of Gospel communication is to enable people to become more like God intended them to be, that is, to display God’s image, then transformation in those who bring the Gospel and in those who hear and receive it will move both toward that goal. This has important theological implications for long-established Asian themes pertaining to maintaining family honor, the awareness of spiritual presence in the surrounding world (what has often been referred to as “animism”) and utilizing worship patterns and styles that are known, understood, and relevant for those who engage in them. God’s will or intent (as I am calling it here), the incarnation through the example of Jesus’ time on earth, and the role of the Holy Spirit, all loom large in this process. The message of the Bible as it works itself out in the Asian environment, and how Asian disciples will themselves be missional, are important to consider. By implication, theological development must be responsive to the environment in which people think about God, that is, in which they theologize. And the theology must begin with God’s perspective in view (from above) which when applied to human concerns about the whole of life (from below) enable people to understand God in a way that makes sense in their context. This is the whole point of incarnation as a biblical theme, it was Koyoma’s point in considering the relevance of water buffalo, and it must be our focus as we consider the impact of biblical theology in context—something very different than the contextual theologies of recent years. The Bible, what God has said, must be the priority as we relate the biblical message to human environments.

When I talk this way, the immediate response is, “that sounds syncretistic”. My response is “from what point of view?” If another socio-religious plausibility structure is the criteria for judging, than anything that does not fit within the schema of that system, is by definition syncretistic. If however, Scripture is the criteria, then every human context falls under God’s scrutiny and syncretism as a construct shifts from what is “wrong” to what is “right”. Once we recognize the myriad of things within a religious system, including their rituals and ceremonies, that match up with God’s intent (at least from the perspective of the people involved) then what does not match can be recognized as needing transformation. When people bring their cultural expectations under the examination of God’s plan for creation, they can make adjustments they consider important for making their experience more like God wants for them. No one from outside that context can make such decisions for people. So, rather than syncretism which is almost always negative (Shaw 2018), we can apply relevance theory to see the nature of the intent-inference equation and make adjustments in the feedback loop that will enable people to realize God’s desire for them. William Burrows and I call this process “hybridity”, making something new out of two different realities; new in that the bringing together reveals elements of both sets of experience (in this case God’s and a given people) that reshapes into something that did not exist before(Shaw and Burrows 2018). There are countless examples in the Bible, often centered on being obedient to God: Abraham, the Tabernacle, the Nation of Israel, the Gospel, Jesus’ incarnation, and the list goes on. Similarly, within socio-religious environments, hybridity happens when people bring Scripture to their context and create new rituals and ceremonies centered on their understanding of Scripture.

ASIAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS HYBRIDITY

I will now apply relevance theory, schema and hybridity to three key Asian themes that have often been confronted as syncretistic from a Western perspective, but central to Asian schema pertaining to ancestry, spirituality and worship. These are maintaining family honor, the awareness of spiritual presence in the surrounding world and utilizing worship patterns and styles that are known, understood, and relevant for those who use them. I will discuss each in their turn.

MAINTAINING FAMILY HONOR

From the earliest days of mission encounter in Asia, ancestors have been a stumbling block—for outsiders, not the local people. For Asians, respect for family heritage and what is often referred to as “filial piety” are as natural and necessary as breathing. It is a schema associated with identity—remove ancestral ties and you take away an Asian’s identity. That is not God’s intent. Scripture is full of references to honor, respect, care, and close interaction with family and a great concern for genealogy. How dare non-Asians take that away! Two chapters in my recent book focus on the importance of different aspects of responsibility toward ancestors, one by Mantae Kim, detailing the Korean ancestral rite (Kim 2018, 85-99), and the other by Yosiyuki Nishioka on the care of ashes and the dignity of honoring the dead at the funeral as well as commemorating special occasions for up to thirty-three years in order to avoid a curse from the spirit of the deceased (Nishioka 2018, 158-172).

For Kim, the observance of the ancestral rite is central to being Korean, especially for the first-born son. The concern for the Korean Church today is how to enable Koreans to be true to their Korean identity and yet remain true to their identity with Christ—what does it mean to be Korean and Christian? He details that struggle through telling his personal story. How he came to faith, went against his family’s wishes and eventually understood the deep pain he caused his father, and gradually came to accept how performing the death rite enables the family to gather and enhances family fellowship. Kim came to appreciate how the deepened sense of belonging is totally in line with God’s intentions for his family in particular and the Korean people in general.

Kim discusses the traditional ancestral rite in its religious, social and psychological elements. In each he sets out principles that reflect Korean schema relating to the role of ancestral spirits and their visitation at the ritual where food is carefully laid out on the table with the ancestral tablet prominently displayed. The social interplay between family members in their spiritual role toward each other and the ancestor ensures respect, honor and gratitude toward the deceased ancestor. Recognizing what each generation has received from its predecessors provides psychological fulfillment and a sense of family well-being and belonging.

In this interplay, Kim presents biblical principles, and establishes how the religious aspect of invoking the presence of ancestors at the ritual table goes against Scripture. Both the social and psychological aspects of the ritual, however, fall closely in line with many biblical precepts that encourage families to recognize and celebrate their heritage, apply their knowledge of ancestral experiences to contemporary life, and relieve family members from remorse and regret that they did not serve their ancestors as well as they should have during their lifetimes. Thus only the religious focus needs adjusting, and a recognition of God’s blessing upon the ancestors, rather than requesting blessing from the ancestors, bridges this important gap. Rather that worshiping the ancestor, Kim encourages Korean Christians to worship God and be thankful for God’s influence on their lives through the experiences of their ancestors. Thus it is God’s blessing that empowers today’s Christians who give honor to and appreciate their ancestors with all the attendant social and psychological implications intact. Rather than laying out food on a ritual table for the ancestor, that same food can be prepared and enjoyed by family members following a worship service in which the traditional symbols are used to give honor and respect to ancestors while at the same time worshiping God in a biblical-centered way that is faithful both to God’s word and respectful of Korean culture. Taken together, these “components are designed to worship God, affirm Korean culture, strengthen believing participants, and impact unbelieving participants” (Kim 2018, 98).

In Japan, properly handling a person’s ashes is essential for connecting and maintaining family ties. Therefore funeral and memorial services that demonstrate proper care of a person’s ashes while addressing the emotional and psychological needs of the bereaved family in a context of connecting invisible spiritual ties between the ancestors and their living descendants is essential for Japanese Christians and non-Christians alike. Nishioka provides a case study of accomplishing this at the Pisgah Ossuary. Through the elaborate use of flower arrangements to tell the story of the deceased and the careful and respectful placement of a person’s ashes in the bone ash space, the deceased is honored. Then, the bereaved can regularly visit and remember the person at strategic times, thereby maintaining the memory of the deceased.

Conducting funerals in this way with the specifics of a person’s history displayed in flower arrangements attracts non-Christians who identify with the familiar cultural symbols and are then willing to hear the Gospel constructed in a way that demonstrates a warm-hearted, Japanese style Christian response to life and death. Rather than being negative to ancestral concerns, people experience the “creator of life, the reality of the shortness of life, and the indispensable value of people whom God loves” (Nishioka 2018, 163). Combined with a careful telling of the person’s life and dignity non-Christians can be drawn to a biblical message communicated through a cultural schema that reflects Japanese expectations which they understand and appreciate. This bone ash imagery conceptually connects with all Japanese, past, present and future, and rings true for those who care about their heritage, appropriately honor their dead and anticipate the future because of what has gone before. When Christians appropriately demonstrate that same care, the Japanese people listen, and consequently blend Christianity into a “Japanese conceptualization of expression that appreciates their story and connects it with God’s story, which may be bridged by the story of their ancestors—those whose bone ashes symbolize their lived story and reflect a humble reality of sense-making” (172).

RECOGNIZING SPIRITUAL PRESENCE

“The spirits residing in the tree could not escape before the tree was milled into planks that were used to build my house. Now they are stuck here and the only way to release them is to call a Monk who can perform a ritual using the Bali language in order to let them go.” Such was the discussion I had in 2017 with a group of Lanna villagers near Chiang Mai in the far north of Thailand. It represents an awareness of spiritual presence that pervades all activity throughout Asia and much of the rest of the world, except the West with its “excluded middle” as Paul Hiebert called it (1982). The imported Western Church has long ignored the importance of animism, the assumed spiritual presence that “animates” everything in the universe, often recognized as spiritual beings (variously named and identified by local people in reference to the environment as ‘mountain spirits’, ‘water spirits’, ‘bush spirits’, and so on), spiritual power (often called ‘mana’ especially in Oceania) that may indwell objects, people, and anything else, and any other manifestation of unusual or unexplained spiritual presence. The manifestations of such presence varies with the context and anthropological, psychological and missiological research all attest to the widespread recognition of such power, as does the Bible.

The issue with respect to animism then is not whether these presences exist (as may be questioned by Western rationalism which assumes something is not real, unless it can be scientifically proven) but how they are experienced, and the import people place upon them. By teaching against such presence, and banning rituals and ceremonies associated with them, missionaries unwittingly guaranteed “dual religion”, that is, the coexistence of Christianity (either in the Church or in the presence of missionaries) and on-going spiritually motivated beliefs and expressions from the reality of the world people lived in, what Hiebert called “syncretism” (Hiebert, Shaw, and Tienou 1999, 22). In point of fact, people were simply applying their spiritual schema to their survival, protecting themselves from spiritual harm which the missionaries’ “religion” completely ignored. This tragic clash of schema has resulted in great confusion, much miscommunication, and a nominal church that is largely irrelevant to the Asian context.

Therefore, my concern here is what happens to the rituals and ceremonies associated with protecting people from spiritual presence. How can the charms and amulets blessed by shaman be brought under the Lordship of Christ and used for their intended purpose while honoring God? How can the countless rituals performed by shaman to keep spirits at bay, drive out demons, and ascertain the nature of such presences be redeemed? Before answering these questions, I wish to look briefly at one more set of concerns that typify religious experience in Asia, namely patterns and styles of worship we see throughout this region where two-thirds of humanity resides.

WORSHIP PATTERNS AND STYLES

Worship patterns are often set by the religion being expressed. The great religions in Asia (Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Shintoism and Confucianism) and their many derivatives and local manifestations emphasize temples, idols, and priests (of one sort or another) who know the appropriate rituals and ceremonies to officiate on behalf of the people who come to worship. The three primary monotheistic religions of the world (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) reject the worship of idols and focus their attention on God who is understood and studied from the tenants of the particular religion and its many expressions by educated, theological elite.

This contrast of worship styles based on monotheism vs. polytheism divides religious expression and forms the contrast which is presented throughout the Bible. The first three commandments speak to this contrast: “Do not worship any god except me, do not make any idols, do not bow down and worship idols” (Ex 20:1-5). This declaration separated the people of Israel from all other people groups who had a plethora of gods represented by idols made of human hands, to whom people regularly gave homage. When Israel strayed from keeping God’s commands and adopted worship styles from the people they mixed with, God brought punishment and ultimately exile and diaspora. While God did not deny the presence of other spiritual powers (a product of Satan’s rebellion and leading a host of demons away from God’s presence), he wanted to be the focus of worship without the assistance of idols and worship styles beyond what he gave the people as they worshiped first in the tabernacle and later in the temple.

God’s desire was to be the focus of worship, which he enjoyed and therefore bestowed blessings on those who worshiped him. The objective of worship was not the forms or expressions but the object—God. It was God who then poured out his grace upon the worshipers. My thesis is that the original intent of worship emanated from God’s interaction with ancient peoples. Because of Satan’s insidious deceit, people shifted the focus from God to obtaining the benefits God provided; protection, care, and shalom. The shift from the object of worship to the result of worship represents a primary cognitive shift from devotion to manipulation. Religion, then, can be viewed as a shift from a focus on God to searching for the benefits God provides and dealing with local manifestations of spiritual power rather than the source of that power. Human attempts to control spiritual power takes control out of God’s hands and puts it in the hands of spiritual practitioners within each religious expression. The elite hold spiritual power over the people rather than giving honor and praise to the one true God. From this perspective, all human religious expression is a product of the fall, and thus, contrary to God’s original intent. How then do we resolve this expression of human sin and return to God’s expectation?

FIGURE 2: A Shift from Spiritual Manipulation

to Godly Worship

(Shaw and Burrows 2018)

It is my contention that the more people use styles of worship they are already familiar with, and adjust them to conform to God’s expectations as revealed in Scripture, the more they will understand and appreciate their worship of the one true God. Figure 2 depicts the process of shifting the focus from survival and manipulation for personal benefit to true Godly worship.

Thus, typical ritual is associated with common practices like salat, puja, temple attendance, appropriate dress, recognition of devotion (things like bindi or tilaka, using mantras, use of music) and many other expressions common to religious affection. If God encouraged people to engage in ritual and ceremony as we see throughout the Pentateuch, and those manifestations were misappropriated, presumably they can be re-harnessed for their intended purpose. Through Figure 2,I seek to provide a process to help people do just that. And by doing so, the emphasis will once again return to honor and praise through devotion thereby allowing God to return his pleasure by bestowing grace upon the worshipers. This process, it is my contention, will reduce nominalism that we so often experience in Christian churches and restore a vibrancy and excitement for worshiping God in ways that not only make sense to the people but bring great pleasure to God.

CONCLUSION

Christianity should not be a foreign religion introduced from the outside and held to regardless of local interests, concerns and cultural patterns. Rather it should be an exhilarating expression of joy that emerges from a desire to truly worship and give honor and praise to the God who created every human being and delights in our devotion and sensory pageantry. God does not want boredom and lack of interest, he delights in our exaltation and in turn pours out blessings and provides shalom, that is, human well-being. Rather than missionary induced styles of worship which often lead to the “tedium effect”, Asians should be encouraged to apply Koyoma’s introductions of theological themes, and Newbigin’s principles of ecclesial relevance, from everyday symbols and interests, to the way they worship, the contexts they worship in, and their postures of worship. In other words, Asian Christians should be encouraged to experiment by applying Scripture to the commonality of Asian life and develop hybrid expressions that reflect their Asian interface with the Bible without inhibition.

The object of worship remains the one true God of the Bible, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the same God who rescued Israel from Egypt, who introduced the Passover, and brought Israel into the promised land which he gave to Abraham hundreds of years before. This is the same God who engineered Jesus’ birth in a humble manger, and used his years on earth to demonstrate, through the power of the Holy Spirit, what it is like for God to truly dwell among his people. But as John’s prologue clearly states, despite his coming to his own, they obviously did not recognize him, he was too much like them, the Godliness they were looking for was not part of Christ’s humanity, and they eventually put an end to his earthly life because he did not fit their expectations (Jn 1:11). This is the same God who energized the beginnings of the Church, transforming timid disciples cowering in the upper room in fear for their lives into a band of energized, almost super-human men and women witnessing in the face of extreme adversity, rejection and martyrdom to build a Church that turned the world upside down (Acts 17:6). Numerous stories from the Acts of the Apostles tell of transforming Judaic rituals into acts of worship in various contexts small and large. How can this happen today in Asia? When Asian Christians take rituals and ceremonies they already know well and apply biblical principles to make appropriate adjustments, non-Christians will recognize the focus on worship. When this happens, I suggest the foreign shackles that have long help the Asian Christian Churches hostage, will be put aside and Christianity will become Asian in form and meaning far beyond what it could be in the hands of outsiders.

In Mark 3:14, and Luke 10: 1-9, Jesus sends out his disciples to change their world. He instructs them to herald his coming, heal the sick, and cast out demons. This pattern was repeated through the book of Acts as the disciples lived out Christ’s command to go to the nations, make disciples, baptize them, and pass on what they had learned from their Lord. This is a familiar pattern around the world, but the intimacy of relationship has often been missing. And in terms of Western rationalism, the reality of demons who need to be cast out, and need for physical, social, and psychological healing has often not been exercised. Within the bounds of the various Asian cultures with their myriad of worship expressions and engagement with spiritual forces, as I have only minimally introduced here, I encourage experimentation; searching Scripture for principles that enable adaptation of ritual and ceremony that can meaningfully restore Asian identity to the churches across this dynamic and expansive region of the world where Christianity has often not taken deep root.

Furthermore, there will be a spiritual break through as well. Watching spiritual beings will take notice and scurry for the dark corners of temples, forests, and high places where the hosts of Heaven will hold them. Liberated human beings, in contrast, will enjoy the great freedom and joyous delight of worshiping God, the redeemer of the world. Asian Christians will be energized by the enabling and equipping spirit of the one true God almighty. To that end I dedicate this essay and pray that this vision of Asians rejoicing in worship will become a reality that transforms Asian Christianity and by extension the whole of the Church.

———————

*This paper was presented at the 2018 ASM Forum, Bali,Iindonesia. Permission was granted to publish this paper on AMA.

========================

R. Daniel Shaw

danshaw@fuller.edu

Dr. R. Daniel Shaw obtained his PhD in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Papua New Guinea. His M.A.Cultural Anthropology, and his B.A.Anthropology/Oriental studies are from University of Arizona. Dr. Shaw is currently the Senior Professor of Anthropology and Translation at the Fuller Graduate School of Intercultural Studies in Pasadena, CA. He also serves as an SIL International Anthropology Consultant. He and his wife make their home in Alhambra, CA..

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.