- January 13, 2020

- Posted by: admin

- Category: advance

Today, Missionary Career Transition is an urgent task that needs to be addressed not only by individual missionaries, but also by the Korean Church as a whole. Recently, we have witnessed an increased number of missionaries who have been expelled from their mission fields. Not only that, uncontrollable circumstances such as family death and sickness, natural disasters, civil war, terrorism, and more, have forced missionaries to suddenly withdraw from their mission field. For these missionaries who have to leave their mission field regardless of their intention or desires, finding a new ministry is not an easy matter. In addition, as the generation of missionaries who have led the historic missionary movement in Korea, the number of missionaries who retire are continuing to increase. If missionaries remain in the mission field post-retirement, it is not easy for them to work with local church leaders with the younger missionaries. However, even if missionaries leave their mission field and return home, it is difficult for them to find a role in a ministry. In contrast, there are missionaries who have no option but to stay in the mission field.

In this article, we will try to understand missionary career transition, examine the need for it, and finally propose practical way to help facilitate missionary career transition among missionaries.

UNDERSTANDING MISSIONARY CAREER TRANSITION

The subject of “missionary career transition” is not familiar in the Korean Church. This is because of the misconception that the development or change in career is only related to secular occupations. In this respect, studying the theological conception of career and the concept of career in the 21st century will help us understand missionary career transition.

Understanding Career through Theology

The term ‘vocation’ that we currently use derives from the Latin word “vocatio.” The German word for vocation is ‘beruf’. In German society today, ‘beruf’ is generally used to symbolize a profession (Holl 1958: 152). In the Roman Catholic Church, the word is still used only as a monk or priest’s “calling.” It was not until Luther’s universal priest doctrine that ‘beruf’ was understood as a profession and not limited to only monks or priests.

Luther explained his doctrine as ‘klesis’(calling), a Biblical concept. The Greek word ‘klesis’ that was used by Paul is synonymous with the Latin word ‘vocatio’. This word is used in the New Testament eleven times (Acts 2: 38-39, Romans 11:29, 1 Corinthians 1:9, 26, 7:20, Colossians 3:15, 1 Thessalonians 2:12, 2 Thessalonians 2:14, 1Timothy 6:12, Hebrew 9:15, 1 Peter 2:9). Luther interprets these verses and defines “klesis”(calling) as “everything that Christians who accept ‘justification by faith’ do in order to serve their neighbor” (Eom 2006: 8-10). This definition leads Luther to leave monasticism in connection with his calling.

Luther also clearly distinguishes vertical and horizontal dimensions in relation to work. In other words, we are saved by faith in our relationship with God (vertical dimension), so we do not need to do any work (act) for God. Work (act) is for serving our neighbors (horizontal dimension). “A righteous man by faith need not give himself to God to be justified. Instead, he gives his actions to the neighbors who need it. When we are faithful in God’s calling, we lead holier lives and we practice the loving of our neighbor in completion with the law (Gal 5:14)” (Eom, 2006: 7-8).

In this way, a job is a calling and a means to serve our neighbors. Because of that, depending on the needs of the neighbor, it is possible to change jobs (careers) to serve our neighbors more effectively. Missionaries do not have to regard their calling to missions as “holier” than other professions. If another profession is more effective for serving their neighbors, it is acceptable to have a different occupation and lay down their occupation as a missionary.

Understanding Career Transition through Social Science

In the earlier days of research on careers, concepts about career were only used for professional occupations such as lawyers or doctors. However, in the present day, career is defined not only as an occupation, but also as an “accumulation of role-related experiences over time” (Hall 1976: 3; Louis 1980: 330).

Role-related experiences include: (1) objective events and situations, such as series of job titles, job duties or activities and work-related decisions, (2) work-related feelings of ambition, expectations, values, (Past, present, and future) of related events (Kim 2007: 27).

Rather than simply focusing on the work of job itself, scholars who are engaged in social sciences today try to understand career through the various meanings and elements associated with work and profession. Different academic fields and scholars base their definition and understanding of career from different viewpoints on the basis of the research in those specific fields. For example, the field of psychology organizes career as a profession, means of self-realization, and personal structure of life. (Arthur, Hall & Lawrence 1989: 10). According to the traditional field of psychology, employment is one of the characteristics of adulthood. In adulthood, an individual expresses oneself through work. As we enter adulthood, we spend most of our time at work, where socialization is cultivated and our lifestyle is inevitably influenced. One scholar who views career as a profession in terms of traditional psychology is John L. Holland. Holland developed the Career Choice Theory through his research on occupation as a self-expression of adulthood (Santroke 2004: 435-438).

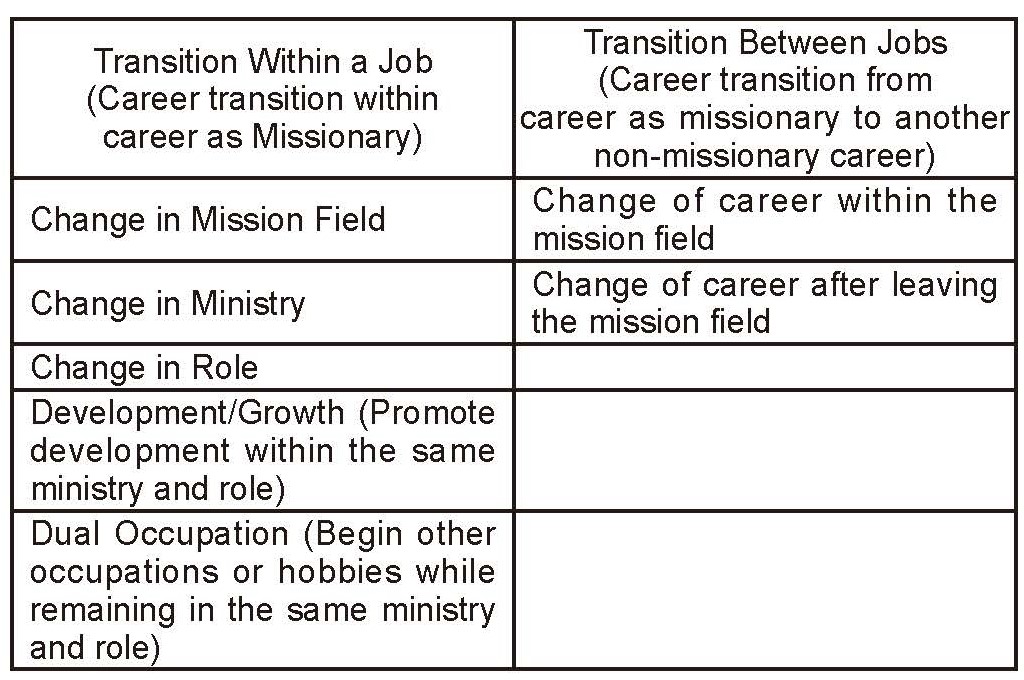

On the other hand, Daniel J Levinson, who studied the life-cycle stages, defined career as a component of a personal life structure (Levinson 1984: 49). Based on this view, he divided his life into four seasons and studied the characteristics and tasks of each season. He then established a Seasons of Life Theory by conducting a study of careers that suit the characteristics and fulfills the tasks required of each season. As such, a career is not simply a type of work or occupation. It is a total of elements related to the work and occupation. Thus, career change refers to changing all or a part of the elements related to the current job. Based on this understanding of career transition, the diversity of missionary career transition can be explained and shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

MISSIONARY CAREER TRANSITION TYPES

Understanding Career in the 21st Century

The 21st century has emerged as the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution where the career world is experiencing an unimaginable amount change. Some predict that half of the existing professions will disappear in 20 years. In today’s world, you do not have to go through traffic jam and go to the office to get a job done.

In the past, career has been understood in relation to a fixed occupation, but today, it is understood that career can be flexible and can be changed at any time depending on changes of the occupational environment. Following this phenomenon, scholars label the 21st century’s career as Protean Career and Boundaryless Career.

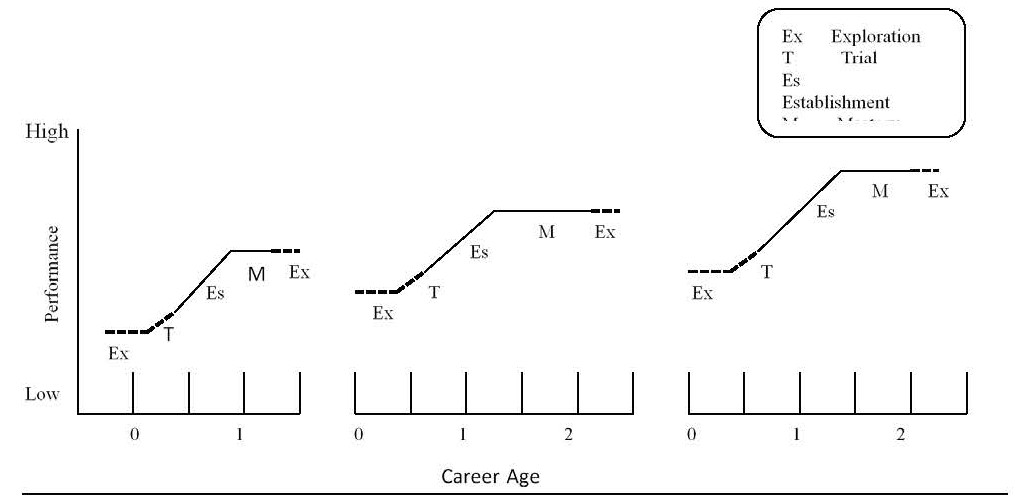

Protean Career is a concept derived from the Greek god Proteus, who freely changed his image according to his will. Lke Proteus, Protean Career views career as something that should be changeable in response to the demands of the 21st century or even to the demands of the career itself. What is emphasized in the Protean Career is that today’s career is not organization-centered but individual-centered, and individuals must constantly reinvest in their careers according to the changes within themselves and their environment. Therefore, individuals must develop their career through continuous learning. Hall, who first coined the term “Protean Career” after witnessing the career phenomenon of the 21st century stated that “The career of the 21st century Protean Career is not measured by chronological age and life stage, but by continuous learning and identity changes” (Hall 1996: 9) and displays a new career cycle as shown in Graph 1. In other words, the career cycle which consists of exploration, attempt, establishment, and mastery of a career in this rapidly changing era is not a one-time event but a cycle that continues to repeat itself.

GRAPH 1

CAREER STAGE: LEARNING VS. AGE

THE NEW MODEL: LEARNING STAGE

(Hall 1996: 34)

If a Protean career focused on the aspects of a career, a Boundaryless Career focuses on the transfer of careers. A rapidly changing environment of employment, and changes in individual values as well as overall changes in life require individuals to expand their career paths, including change or transfer of occupation and company. Michael B. Arthur, who focuses on career path expansion, offers a new perspective on career using a concept he calls Boundaryless Career. In Boundaryless Career, individuals do not just stay in a specific department within an organization, rather, they move to various departments and even move freely from one organization to another. This Boundaryless Career departs from the single employment situation and provides multiple employment and ongoing career opportunities (Arthur 1994: 303-304).

Career opportunities are also concomitant with challenges. For example, the reduction of personnel due to the reduction or reorganization of companies and the emergence of new jobs challenge individuals to develop competencies related to their jobs. The competencies that individuals have been able to use in their working environment so far, such as the skills and knowledge about a specific job (know-how) or the relationships built (know-whom), may become irrelevant in the future. In these instances, there may be confusion and conflict in their identity (know-why) (Arthur & Defillippi 1994: 311). In order to respond positively to these changes in the career environment, the Boundaryless Career has the following features. First, individuals strive to acquire knowledge and skills that can be used in various working environments. Second, individuals establish a wide variety of networks including interpersonal relationships, customer relations, and mentoring programs. Third, there is a shift from the employment relationship between individuals and organization to a personalized career, which gives personal meaning to work (1994: 311, 312). Table 2 compares the characteristics of the Boundaryless Career with the characteristics of the traditional career.

Table 2

(Comparison of Tradition and Boundaryless careers)

(Sullivan 1999: 458)

As shown above, the understanding of the traditional concept of career has changed drastically as we entered the 21st century. The new career paradigms, Protean Career and Boundaryless Career, are focused on the individual rather than the organization, and are value-oriented and self-directed. Rather than settling in one career and acquiring the necessary skills for that career, the focus is placed on continuous learning, which can build skills that are transferrable from one career to another.

Understanding concepts about career in the 21st century also requires missionaries to change their predated understanding of career. Missionaries must realize that the subject of a career is an individual, not an organization, as the Protean and Boundaryless Career maintains. While a mission organization or a church’s help may be needed for career transition, individual missionary must take the lead and manage his or her career with freedom.

Organizational Change for Career Management

In the traditional concept of career, the organization and society had a great role to play. In the organization-centered career management, there was a psychological contract between the organization and individual in which the employee committed their loyalty to the organization while the organization ensured the stability of the individual within the organization in return. However, these kinds of psychological contracts have been undergoing significant changes as a result of individual growth and adaptability (Hall & Marvis 1995: 270). These changes in career require not only individual changes, but also organizational changes in response.

For missionaries, the same is true of mission organizations and churches. Mission organizations and churches that are focused only on expanding their size and ministry as they did in the past will not be able to secure loyalty from their members, making it difficult to keep the organization healthy. Mission organizations and churches should focus on the growth and development of individual missionaries and provide an environment in which they can effectively develop and transform their careers. The task of exploring one’s own character and exploring the appropritate environment for their unique character, to ultimately discovering a career or position to achieve their career goals goes beyond the capacity of the individual. Therefore, mission organizations should provide tools to help missionaries identify their characterisitics and help introduce and connect missionaries to a work environment appropriate to their characteristics.

NEED FOR MISSIONARY CAREER TRANSITION

Changes of the World

In contrast to previous centuries, the 21st century we live in is a time of rapid changes. These changes created a new career environment, and resulted in the new career paradigms of Protean Career and Boundaryless Career, in which career paths can freely change.

In the past, a single, lifetime job was desireable. Similarily, the missionary’s career in cross-cultural missions meant that he or she would spend his or her entire life as a missionary. By 1893, when SIM (Serving in Mission) was found, Africa was called the “White Man’s Tomb.” True to that name, two of the three founders of SIM lost their lives to malaria within one year of their arrival to Nigeria (Fuller 2007: 2). During that time, many missionaries went into missions knowing that it meant they would die in missions.

However, the world has changed drastically in a way we could not imagine. Charles Van Engen emphasized that the church, which exists to face the world must continue to recognize and accept new paradigms with realistic plans and objectives for the changing world (Van Engen 2014: 63-67). He also states that, “The true essence of the church remains unchanged. However, the church must constantly change and develop to reveal new features” (2014: 64). In other words, the times of cross-cultural missions overseas when transportation and communication means were not developed are quite different from the present times when the world is united through the Internet and SNS.

When mission does not respond appropriately to a changing world, it becomes closed from the world. Emerito R. Nacpil, a Philippine Bishop, stated: “The current structure of mission is now dead. The first thing we have to do is to praise it and then bury it.” Mission seems to be the greatest enemy of the Gospel. Indeed, “The best missionary work that missionaries under the present system can do in today’s Asia is to leave Asia! (Nacpil 1971: 79: Bosch 2000: 762). ”

The cry of this missionary moratorium is now being heard not only for Western missionaries but also for Korean missionaries. The churches in some Asian countries are starting to cry out for Korean missionaries to leave their country. In fact, some Korean missionaries say that ‘Only when Korean missionaries leave can the national churches live’.

A missionary is a guest in the host country and is someone who has to eventually leave it. If you remain in the mission field to find the meaning of your existence as a missionary, or simply to sustain your ministry, it is an abandonment of your stewardship and inevitably harms the mission field. Missionaries should move away from the title of missionary and work in fields and positions that contribute more to missions. If our identity is rooted in mission, we must honestly look for the most appropriate place to partake in the expansion of the Kingdom of God, whether we have the title of a missionary or not.

Changes of Missionary’s Life Stage

Research on career development began in four different disciplines: differential psychology, developmental psychology, sociology, and personality psychology. Among them, developmental psychologists have found that individuals and families have a role to perform or a task to solve every cycle during the life cycle. In addition, while a lifecycle varies from person to person, the order of steps and tasks to be performed are similar and connected (Santrock 2004: 45-46). Daniel J. Levinson, in his Seasons of Life Theory, compared adult life to variations in the season. Just as the seasons change periodically, adult development involves changes from one stage to another. These changes or transition, is required when moving from one stage to the next. Each season of life has its own characteristics, just as each season in the year has its own time and unique color. In addition, each stage makes a unique contribution to life, just as one season is not superior or inferior to another season (Levinson 1986: 4).

The first era, pre-adulthood, is from birth to age 22, including early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and Early Adult Transition. This era is marked by a period of growth, and is a time of dependency and high vulnerability, making the relationship with family members or close caretakers very important. The period of Early Adult Transition, around 17 to 22 years of age, links adolescence and early adulthood. It is a part of both stages, but not a whole part of any one stage. In other words, it is a time when an individual, seemingly mature, yet still childlike, is about to enter the adult world, (2012a: 49).

The second era, Early Adulthood, is from the age of 17 to 45 and ends with a transition period in the middle age of adulthood. This is the time where energy and abundance are at their peak, and conflict and stress are also at their highest levels (2012b: 39). Approximately 40 to 45 years of age is another crucial turning point in life, a middle-age transition period that marks the end of the early years of adulthood and begins middle age. It is a time to step onto the top of your life.

The third era is Middle Adult, which starts from the age of 40 and lasts until 65. Most of the people in this period are the elders of their society. All the responsibility falls on them, especially the responsibility of the development of the early adult individuals, who will be the future elders. On the other hand, during this period, many people experience crisis as physical, mental, and social changes take place. According to Levinson, “experiencing a crisis at this time is not itself pathological. In fact, people who pass through this period without much complaint are refusing to change their lives for better or for worse. People in these conditions can sometimes make the wrong decisions. If we are to live wisely, prudently, and patiently during this era, the crisis of the middle age is an opportunity for self-realization and social contribution.

The fourth era is the Late Adult, which starts around the age of 60. This era is similar to an abundant season in which fruits are tasted and all things are accomplished. The late adult transition period is between the ages of 60 and 65, but an individual can fall into decline, not growth, due to physical illness, retirement, and bereavement with close people. During this period, it is necessary to recognize the characteristics of the late adult era and fulfill the proper tasks accordingly, so that they can finish their lives well and provide a generous space for generations to come. Levinson expresses the concerns that may arise if he becomes immature in his late adult life.

If he does not give up his authority, he is likely to become a despotic ruler – despotic, unwise, unloved, unloving, and his adult children will be immature adult who cannot love their parents or themselves. In a professional life, if a man sticks to a formal authority until he is sixty-five or over seventy, there will be serious problems. If there is such a person, he is out of his own generation, and he can be in conflict with a middle-aged generation who needs to take on more responsibilities (2012a: 72).

Life has its own roles and responsibilities depending on age. In addition, while the individual’s development and the needs of family members or communities differ in degree, life has to be colored according to the season. A young 30-year-old missionary will be able to grab the Gospel and hold onto young children on the barren grounds in Africa. On the other hand, it may be difficult to expect a middle-aged missionary in his 50s who feels the weakness of the body to live and work in remote areas. Middle-aged missionaries can use their experiences and knowledge to work in a different role to train young missionaries, which would be harmonious and desirable in the mission community.

MISSIONARY CAREER TRANSITION METHOD

Missionary Care Transition Assistance Program (Missionary CTAP)

In San Diego, California there is a career transition program for veterans (Vet CTAP: Veteran Career Transition Assistance Program, https://www.vetctap.org). This program helps veterans and their spouses find a stable job. Not only have veterans been away from their home for a long time, they also have difficulty adapting to everyday life after returning home because they have had to live a life different from the ordinary.

Missionaries are like veterans. Missionaries have many difficulties when they return to their home countries because of their isolated life. Especially from the viewpoint of vocation (job, work), they worry about what to do in the future. Along with the individual missionaries, Korean churches need to be concerned and should assist the missionaries returning from the battlefield.

Within the context of Korean missionaries, I would like to introduce a career transition program called Missionary CTAP, which will be presented in three stages. The first stage is the ‘Change in Perception,’ the second stage is the ‘Overcoming Obstacle,’ and the third stage is the ‘Resource Discovery’.

Stage 1: Change in Perception

The first step in the Missionary-CTAP is to help missionaries gain the correct understanding of career transition. Paul McKaughan says it is a new opportunity the Lord has given to the problem of dropping out of missions. Missionary experience of cross-cultural ministry is a precious resource that can be used to expand the kingdom of God no matter what he or she does in the future. However, due to the existing perceptions of missions and missionaries, these resources are failing to function properly. Now, it is necessary to be free from past expectations through a good understanding of occupation, calling, mission, and age (McKaughan 1998: 38).

In order for Korean missionaries to have an effective career transition, the following four levels of awareness or understanding must be achieved.

First is the need to understand career and career transition. According to my research (Cha Nam Jun, 2017: 89), the term “career transition” is unfamiliar to Korean middle-aged missionaries. In a questionnaire asking whether or not they heard about career transition, 124 (43.5%) out of 285 responded that they did not hear about career transition. It would be absurd to try and help with career transition if missionaries do not even recognize what career transition is.

Second, there is a need to shift the perception of calling. In the same study, 105 respondents (37%) of 285 respondents indicated that they were most concerned about career changes. In addition, all of the 16 interviewed respondents stated that they were the most concerned about the call to career transition. Because of the perceived perception of calling, missionaries view career change as a betrayal of their calling. Although some may understand that career change is necessary, they believe that a call to be a missionary is a special calling, and therefore requires a special calling to change careers.

Third, there needs to be a change in the perception of missions. In a questionnaire survey asking about the necessity of career conversion, 111 of the 285, 39% of the respondents answered that there was a need for career change because the Korean church, mission field, and world are changing rapidly. Still, only a small number of missionaries are seeking a change of ministry (19.8%), change of mission field (18.2%) and change of occupation (4.6%). This may be due to the misperception of missions. Missionaries do not think about mission as a whole in terms of God’s mission, but recognize only existing cross-cultural missions as mission. This may be due to the fact that the dualist thinking which distinguishes the missionary career as “holier” than other professions and job is still prevalent.

Fourth, there needs to be an understanding of middle age. There are many factors that middle-aged missionaries need to consider when trying to make a career transition. Among the survey respondents, 29 missionaries (11.2%) mentioned the physical considerations such as age and health. In addition, family (18 individuals, 6.4%), children’s education (8 individuals, 2.8%) and psychological (6 individuals, 2.1%) considerations are also among the characteristics of middle age. When understanding the physical, psychological, and relational characteristics of middle age and making corresponding preparations, middle-aged missionaries can escape from a vague sense of crisis and meet a new stage of life.

In order to help missionaries understand and change their perception of career transition, we suggest the use of a seminar on career transition. A seminar format, which can be done with fellow missionaries who are also worried about career change, can be more effective than one-on-one coaching. Jack Mezirow states that it’s important to share one’s dissatisfaction with the transition process and one’s problems in the transition process with others. The process of transitioning to a new perspective can often lead to the experience of disconnections or heterogeneity in relationships. The sense of loss in relationships can be replaced by a new relationship and a new identity because it is with those who understand and share similar experiences. It is a source of great strength and encouragement for each other to form a relationship with people with the same mind and to share new perspectives and difficulties. It is also important to help them look objectively at critical evaluations of themselves through healthy relationships (Mezirow 2000: 306-309).

Stage 2: Overcoming Obstacles

The second stage of Missionary-CTAP is helping missionaries overcome obstacles when trying to make a career transition. One-on-one coaching is effective at this stage, along with career transition specialists. The career transition specialist can see what factors become obstacles to career transition and help missionaries find ways to overcome these obstacles. If the missionary does not overcome those obstacles, it will not only make a smooth career transition impossible, but will also make it harder to try.

Stage 3: Resource Discovery

The third stage of missionary-CTAP is to find the ‘resources’ that missionaries need in order to to make a career transition. The resource discovery phase also uses a variety of examining tools in a one-to-one coaching format with career transition specialists to identify the internal resources that the missionaries have. It also helps to identify external resources needed to effectively use those resources.

DISCOVERY OF INTERNAL RESOURCES

Based on Parsons’ traits and factors theory, career transition specialists help missionaries identify the internal resources they own and understand themselves and the characteristics of their environment. In order to search for a new career, the following aptitude (ability) test, job interest test, job value test, personality test, etc. are conducted. In addition, one-on-one coaching is conducted based on the results of each test.

Missionary CTCMP (Missionary Career Transition Crisis Management Program)

It is a great crisis for missionaries when they have to suddenly evacuate the mission field because of missionary expulsion, visa rejection, natural disaster, civil war, the missionary’s own disease, and family death or illness. It is not easy for missionaries in this crisis to deal rationally with their career change. They are very tired spiritually, emotionally, and physically. They often try to solve their problems themselves, but they realize that many problems are beyond their ability to solve. Therefore, missionaries desperately need individuals or organizations that can take care of them spiritually, emotionally, and physically.

Rosemarie Rizzo Parse believes that the first thing to do for those in need is “Being With” and allowing the person to share their experience with someone, rather than using their professional skills and trying to rescue them from the situation. In addition, rather than trying to analyze their experience, the counselor should stay focused on the client’s experience by following the flow of the client’s words (Parse 1995: 122-127). In other words, the client should form a sense of intimacy with the counselor so that his / her feelings can be comfortably conveyed.

Most missionaries who involuntarily withdraw from the mission field suffer from negative feelings such as rejection, loss, shame, fear, and guilt. Missionaries should be able to recognize and express these feelings. If the emotions are not recognized or appropriately expressed early in the transition period, a critical evaluation cannot begin and individuals will be caught up in negative emotions and unable to accept a new reality (Mezirow 2000: 291). Once these emotions are properly dealt with through decision making, positive thinking, healthy human relations, and accurate emotional communication, can the individual move on to the next stage (DiMarco 2000: 10).

The second step is to identify the core of the problem by ‘Boiling Down the Problem’ and help the client look at the crisis situation rationally and objectively. The counselor should ‘extract-synthesize’ the emotions of the client with who the counselor has now formed intimacy. The counselor should extract the main content of the experience from the record of the client’s language, compile it in the language of the counselor, and then find out the core concept and find a constructive helping method.

The third step is to actively cope with the problem with ‘Coping Actively’. In other words, it is the step of encouraging the client to positively solve the problem by using the internal and external resources that the client owns. At this stage, the Career Transition Assistant Program (CTAP) should be introduced to determine whether to deal with steps 1, 2 and 3 step by step, or only step 3 without having to go through steps 1 and 2.

Among other cross-cultural missionaries, there are many who experience crises similar to those experienced by Elijah in the Bible, such as exhaustion, deportation, retirement, and inevitably mourning, that require a career change. Missionaries in these crises are experiencing double and triple pains due to physical, emotional, and spiritual isolation. Like God who has touched, fed and put Elijah to sleep, it is necessary to be with missionaries who are exhausted through missionary member care (Achieving Rapport).

CONCLUSION

The environment of the mission field is rapidly changing. Depending on the country, some types of mission work is no longer needed and a new kind of ministry is required. No matter what the mission field is, missionaries with experience and expertise are needed. Even if the local church wants a missionary to come, the host governments are not accepting foreigners without expertise. Also, as the number of leaders and experts in the nation grows, the need for existing missionaries diminishes. Remaining in a mission field that no longer needs you is not only a waste of your life, but can also interfere with the spiritual growth of the area. Therefore, according to the changes that come with time and place, a missionary should prepare for the transition of his or her role or ministry in anticipation of those changes. If such attempts are impossible or ineffective, they will have to leave the country, or even turn their missionary work into another career.

Helping missionaries make the right career transition is not only helpful to a missionary’s life, but is also healthy for missions. Missionary member care organizations should be prepared to help missionaries who are deported from their ministries, missionaries who remain in ministry and are struggling with their role and ministry, and also individual missionaries prepare for the future and get ready for career transition. In addition, we should prepare professionals related to career development or career transformation, and work with missionaries to identify their talents, experiences, and knowledge to guide them to a career most appropriate for them.

===================

Nam Jun Cha

njeom1@gmail.com

Dr. Cha was sent to Ethiopia by GMS and was involved in literacy, adult education, and children’s ministry with SIM for three terms. Dr. Cha has MA degrees in Christian Counseling and in Mission Studies. She earned a Doctor of Intercultural Studies and received the 2018 contextualization award for her dissertation “A Study on the Career Transition of Korean Midlife Missionaries: With Special Reference to the Rodem Missionary Care Ministry” from Fuller Graduate School. Dr. Cha specializes in counseling, debriefing, and career transition. She is serving at Rodem Missionary Care as the general secretary. She also is the founder and president of the Missionary Career Transition Center.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Really give me some inspiration point and consider some part of mission ministry which current mission work by doing Korean missionary. Korean church should concern to retired missionary to return to home field. But most of senior and veterans are seems to be stay longer at mission field for some reason. That is a big worry to Korean church in terms of doing healthy mission. Thanks for a article