- March 29, 2018

- Posted by: admin

- Category: advance

Esther Lee Park

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Many nations in Asia and Africa won their independence from the super strong imperialists in the 20th century. These countries also have been through times of political convulsions under the military regimes and historical transitions to democracy. The wounds of these nations from the past, especially from foreign exploitations are not completely healed. Even, today, the people from these hurting nations, somehow show their suspicions or overly sensitive reactions toward foreigners, including missionaries. I hope this article will contribute some thoughts for the cross-cultural workers, how important knowing the culture and the people of the countries where they are working. My observations and studies are confined in South-East Asia, particularly in the Philippines where I served as a missionary for 17 years. The following is an exemplary study of the Philippines.

A. Effects of Colonialism

Colonialism affected every area of the Filipino life. Everett Mendoza, points out the outcome of colonization in this country: “the external pressures of colonial imposition distort existing mechanisms of resources allocation, disturb traditional patterns of social relationships and interactions, and break down structures of ideas that give order, orientation and meanings to every aspect and the whole of social and personal existence.”[1] For that reason, the Philippines became one of the most cosmopolitan in culture among Asian countries.[2]

– Lack of National Identity: The Philippines suffered from long history of colonization. Some critics argue that even though the Philippines became politically independent in 1946, earlier than most of its neighbours, the country and its people still lack a strong identity as a nation. For an explanation, a foreign writer named Niels Mulder rationalises the lacking allegiance to the nation as, “of all things, independence was not the fruition of nationalism. It was not a product of struggle.”[3] By transferring state leadership to the Filipino elite from the government of the United States without much involvement from the majority of ordinary people, neither event had a chance of having a nation-building impact nor did it lead to popular mobilization.[4]

– Regionalism: Bautista points to two negative traits that in his view explain the weak national consciousness among Filipinos: strong regionalism and the colonial mentality. Tujan, on the other hand, identifies two social structures Filipino society suffers from: the system of patronage and a colonial mentality.[5] Bautista continues, “regionalism is the tendency of a person to be strongly attached and exclusively protective by the members within his group”.[6] Constantino explains that this regionalism, especially by demographic and cultural segregation from each other, enabled easy conquest by both Spaniards and Americans.[7] Tujan points out the ill effects as “that in spite of the fact that the Philippine state has been liberated from their colonizers, but allowing foreigners’ domination on economy, politics and culture causes a politico-cultural system of patronage that has no concept of individual self-worth or self-determination but only of one’s position in relation to the patron”.[8] This regionalism became an obstacle to build a national identity and a barrier to cross for missionary work.

– Fusion Religion: Despite the predominant Catholicism in this country, some indigenous, pre-Magellan, religious traits have been embedded deeply in Filipino religious concepts and practices, both in sacred and daily life.[9] Mulder notes that when speaking generally of Southeast Asian religions, the focus is not on morality or salvation or liberation, but rather an animistic quest for power, potency, and protection (protective blessing — safety from danger and misfortune).[10] He continues, “implicit in this view is the conviction that power is near, tangible, and accessible.”[11]

– Christianized Bathalism: As is commonly known, folk-Catholicism, or Christianized animism, is the dominant belief system of the majority of the Philippine northern and middle islands (Luzon and the Visayas) while the southern Philippines is dominated by Islamized animism or Christianized Bathalism (from Bathala ‘God’).[12] However, overlaid on these synthesised religions, Filipino religious psychology can be found in traditional, indigenous, Anitism (from the word anito, an ancestral god), and it is deeply rooted in various aspects of life.[13] Mulder gives an example of Filipinized Spanish Catholicism in anito worship: ‘this fitted nicely with the local belief in the active role of the recently deceased in the lives of the living. Even today, departed parents and grandparents are often supplicated, and supernatural intervention in human affairs is “naturally” expected in many areas of life’.[14] He continues by explaining the Filipino concept of honouring deceased parents and grandparents, since they were sources of blessing while alive or even after death. Mulder puts it this way: ‘the only line between life and death is as fluid as the line between the visible and the invisible. These are not separate realms but interpenetrate each other, religious manifestations being pervasive and present to the senses…’.[15]

Therefore, outwardly, the majority of Filipinos say they are Roman Catholic as Spanish orientation lies in their culture. Henry describes the fusion of animism with Hispanic Catholicism as ‘the fusion of two separate thought and behaviour systems and the coexistence of two religions in the same person without inconsistencies’.[16] The similarities were well adapted in Filipino religiosity and practices.

B. The Voices of Missionary Moratorium

In the 1970s the voice of “missionary go home” in Africa and Asia shook the Christian community. The causes were several factors, but one thing was clear about a sullen word regarding missionaries’ attitudes. Unconsciously or unintentional attitudes of missionaries who engaged the missions in those areas were provoked by the Christian national leaders. The voices were loud enough that some Western mission organizations ended up withdrawing their missionaries. However, Korean missionaries, after the Western missionaries—were poured out in these areas as replacements. Due to this, I would like to discuss about the cultural clashes in this section which is the main cause of miss-communication happens in general.

C. Cultural Clashes among “Doing Culture” and “Being Culture”

Growing up and residing in a community, people inevitably internalize the commonly shared practices of the group, values that form the basis of their ways of thinking, expressing, and evaluating things in their surroundings.[17] Ultimately, these values also become their own standards for certain ways of decision-making and behaviours when they are a part of organisations.[18] For that purpose, I aim to explain the different value systems and behaviors in both “being culture” and “doing” culture societies. Interestingly, some scholars claim that even among Asian countries there is a clear distinction between Confucian and non-Confucian societies. For example, Jack Scarborough distinguishes ‘doing’ culture from ‘being’ culture like this: “the primary difference is that the Confucian culture is a ‘doing’ culture, whereas the non-Confucian is a ‘being’ culture.”[19]

We need to study both cultures in order to compare and evaluate without passing judgment on others. For instance, in order to reduce the perceived differences between cultures, the technique needs to focus on the individual level rather than the cultural level and functionality of differences. And differences should be addressed in a contextualized way. Providing a reason for their existence makes for better cognitive acquisition of concepts rather than simply stating cultural differences.

Here I will compare two distinctive cultures: Korean culture as a ‘doing’ culture and Filipino culture as a ‘being’ culture. Scarborough continues with a further description of the uniqueness of these world views:

‘Doing’ cultures are more individualistic, are more masculine and competitive, and have smaller power distances. Very much different from ‘being’ cultures, wherein people tend to be weak in uncertainty and tries avoidance, not out of submission to fatalism, but rather because they are conditioned to bring about change proactively. They want to build a more perfect world rather than enjoy the world as it is. ‘Doing’ people tend to define themselves according to their occupations and measure themselves by their achievements. ‘Being’ cultures tend to be more relaxed, more holistic in their world view, more relationship-oriented, and more accustomed to yielding power; view time as a continually recurring cycle; feel less able to control their fate; and want work, which at best can be enjoyed and at worst can be tolerated as a necessary evil. ‘Being’ people define themselves by their collective affiliations. They ‘work to live’, whereas their ‘doing’ counterparts ‘live to work’. ‘Doing’ people see ‘being’ people as lazy, unproductive, and irresponsible. ‘Being’ people see ‘doing’ people as cold, compulsive, and unable to enjoy life.[20]

1. An Example of “Doing Culture” Background: Koreans (missionaries)

– Confucius world view: Confucianism and Koreans cannot be separated. George Paik, a Korean Christian historian, testifies as

…it was Confucianism that formed the character of the people and shaped the course of the ancient civilization of Korea. Korea accepted the imported system and made it part of the bone and fiber of the people. In return, Confucianism made distinctive contributions to the development of Korea.[21]

The effects of Confucianism, Paik writes, had many deplorable results: “it nourished pride, taught no higher ideal than that of superiority,[22] and was agnostic and atheistic in its tendency; it encouraged selfishness, exalted filial piety…and it imbued every follower with a hunger for office.”[23] The effect of Confucianism on Korean society was controversial: some say its systematic higher and lower concepts have been a hindrance to their becoming a healthy democratic society. Others say it created a balanced life from a fast-paced and changing society. However, most people observed that one Confucian heritage, enthusiasm for education, is undoubtedly a main contributor to the modernization of Korea. Foreign observers conclude that the traditions of Confucianism and the needs of a modernizing society coincide for “not only natural but perhaps even inevitable that Koreans would transfer their traditional respect for learning to the task of mastering new technologies from the West.”[24] This positive influence from Confucianism is from a ‘self-cultivation’ to reach virtue: It provides the fundamental source of insight and strength to rule orderly within oneself, one’s family, one’s country, and abroad.

2. An Example of “Being Culture”: Filipinos (local church leaders)

– Equilibrium-maintenance worldview: As I mentioned earlier that the effects of long history of colonization made the definition of Filipino difficult. The general notion of ‘Asian is Asian’ becomes confusing when it is applied to Filipinos.[25] Historically, the Philippines has been under the influence of Western contacts for a long period. The Filipino is Asian but cannot be considered entirely Eastern.[26] The complexity of defining the Filipino is, as Bautista writes, “in a highly stratified country like the Philippines, defining the members of the set of Filipinos can itself be a problem.”[27] Therefore, this study will focus more on the indigenous psychology of Filipinos that has survived throughout the centuries: their basic temperament and lifestyle. Mercado employs the phrase pagkakapantay-pantay,di pagkakatalo “equilibrium-maintenance” as the Filipino concept of being in harmony with nature. They calmly accept the continuation of natural catastrophes such as storms, floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions and learn how to adapt in this harsh environment. Therefore, if this balance is disturbed, the Filipino expects suffering and other forms of misfortune.[28] This equilibrium-maintenance with nature also applies to everyday life and interpersonal relationships. Well-known Filipino communication skills such as avoiding conflict, smooth interpersonal relationships (SIR), and group consensus are ways of coping with the disruption of peace and accepting pre-ordained destiny.

3. Comparison

It is evident that two people raised in different worlds easily become judgmental toward those from the other culture. Management practices in an office can become problematic since two groups of people follow different work ethics and hold a different general world view. Filipino anthropologist, Landa F. Jocano emphasizes the art of Management By Cultural awareness (MBC): “In the office, the tasks may be technical in nature, but motivating people to peak performance is cultural”.[29] He goes on to say that MBC is the new key to achieving teamwork and cooperation:

“…foreign techniques may be academically attractive, but they are seldom suited to the Filipino cultural temperament; effective management is the function of fit or match in the perceptions and expectations managers and workers have of each other.”>[30] I think that comment also can be applied to missionaries who work in cross-cultural settings.

In Korean culture and management, it is almost impossible to escape the hierarchical structures which have been embedded in Korean homes and society. Therefore, for people who were born and raised in this environment, Confucius’ five-fold proprieties would obviously be a dominant theme between leader and subordinate; it is a monolithic, regimental management style. Even if the subordinate is more knowledgeable and able to handle things better than the boss, the position is territorial and cannot be crossed over. Scolding a person in public (during meetings) in a Philippine setting — a common and expected practice by the boss in Korea — can provoke anger among Filipinos. Therefore, in the Philippines, communication is always indirect and non-adversarial. Under the Filipino cultural norm where everything is relational (Smooth Inter Relationship, SIR), Korean missionaries’ unconscious actions stemming from their Confucius psyche produced a rather poor acculturation outcome. This exogenous relational gap could affect the competency of the mission work: its performance, quality, and productivity.

The following three steps are the traditional ways Filipinos use to communicate and arrive at decisions for the group: “pagsasangguni (consultation)”, “paghihikayat (persuasion)”, and “pagkakasundo consensus).”[31] An example, the reclusive planning of the growth strategies by Korean missionary executives, without inviting their local counterparts—only requesting them to join at the implementing stage instead of the brainstorming stage—has been the usual practice by foreign mission leaders and has created resentment against missionary leadership by the majority of national leaders. Therefore, the practical use of “consultation” seems to be the only solution to remove clashes at the top leadership level. Jocano continues that this functions more than just as consultation, but it shares the responsibility by getting people to participate in planning. Also, “consensus” can be a helpful tool to boost team spirit since everyone agrees in the group, but it can become a sumbat (may be translated as reprimand or reproach) or moral censure if planning is not done as a consensus.[32]

D. Misunderstandings and Improvement of Culture Sensitivities For A Better Communication

Culture can be observed on a surface level related to language, food, and behavior, while on the deeper level they relate to beliefs, feelings, and values. As Hiebert points out “misunderstandings are based on ignorance of beliefs, feelings and values of another culture”[33] :

- Ideas, the cognitive aspect of culture, have to do with the knowledge and wisdom shared by members of a group and provides the conceptual content of a culture.

- People’s feelings, notions or standards of beauty, likes, and dislikes, etc., are the affective dimension of culture reflected in most areas of life.

- The evaluative dimension of culture has values to judge human relationships:- moral values such as ‘moral’ or ‘immoral’; cognitive beliefs to determine ‘true’ or ‘false’; emotional acknowledgment of ‘beauty’ and ‘ugliness’. Also, this stage of the dimension contains each priority in values and primary allegiances.

These three cultural dimensions are indispensable for understanding the nature of each group or society. Therefore, this cultural study between Korean and Filipino cultures focused on these cognitive and behavior dimensions. So, it is a necessary process for national leaders to constantly interact with their foreign colleagues to develop a learner attitude in understanding missionaries in order to improve communication and achieve common goals. Ideas, the cognitive aspect of culture, have to do with the knowledge and wisdom shared by members of a group and provides the conceptual content of a culture. Also Scarborough suggests that both the ‘doing’ culture and the ‘being’ culture learn from each other on how to modify for the harmony of the organisation: ‘we may need to be satisfied with simply learning from one another. Although it is assumed widely that those from “being cultures” could do with a little more “doing”, it may well be that those from “doing cultures” could benefit from being a bit more “being”.[34] Heibert suggests that the solution to misunderstandings and premature judgments toward cultural differences is empathy: one needs to learn to appreciate other cultures and their ways of life.[35] This sense of openness leads to a deeper cross-cultural sensitivity that allows individuals to think as members of the other culture.

SUGGESTIONS

1. Need for Improved Missionary Cross-cultural Training

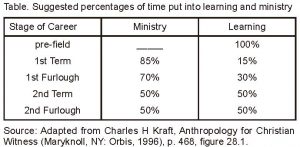

In interpersonal matters, many missionaries were unprepared. This has raised concerned voices from missiologists, especially those who have served as missionaries themselves and specialize in the field of cultural-anthropology. For example, Kraft suggests that the main focus should be to have a learner’s attitudes: to learn how to learn. He talks about the problem of our school experience where we are pressed to learn how to be taught, not how to learn.[36] Our general system of education there is no room to ‘add’ once you complete the education. It is a different skill to learn. He emphasizes that if a missionary has a learner’s attitude, they will then carry this attitude to the field. He adds the suggestion that during a regular furlough period, missionaries could spend at least part of their time in analysis and reflection. The chart below is Kraft’s suggestion for percentages of time a cross-cultural worker should put into learning compared to how much time into ministry; I believe this would be definitely profitable for the cross-cultural workers.

2. Self-awareness and Self-directed Cross-cultural Training

Dale Kietzman points out that the first step in the cross-cultural training is self-awareness. He writes of the importance of cross-cultural training as follows:

Cross-cultural training cannot prevent cultural shock, nor bypass the experiential unease of actually living with people of a different culture. Cross-cultural training can, however, point the way to becoming a self-directing person, able to learn from life in the new foreign context. Cross-cultural training can increase awareness, provide a foundation for understanding another culture, for developing skills through experiential processes, and reducing the anticipated anxiety of living and working in a new cultural context.[37]

Kietzman is also vocal against missionaries having leadership roles in projects involving international teams if they have failed in their adjustment to other cultures.[38] It is also a common sense that if leadership is defined as ‘influencing others’, then a person who has not developed leadership skills recognized first within his own society, he probably will not develop as a leader in cross-cultural contexts. Kietzman continues, “the characteristics of a leader, the sensitivity to followers, the ability to take initiatives and to do strategic planning, however, should all be transferable to another cultural setting, if the leader’s cross-cultural training has created a true cultural sensitivity and a desire to be a life-long self-motivated learner.”[39] This claim seems logical, yet many Korean churches and mission agencies neglect a very basic and simple screening process that acknowledges that people do not change easily. A careful selection of individuals through their histories of performance in their homeland should be considered in the missionary selection process.

3. Selection of the Cross-Cultural Trainers

One of Kietzman’s notable suggestions relating to cross-cultural training is about the selection of trainer. He suggests that the best trainer is the one who comes from the same culture as the trainee.[40] He mentioned earlier that the first step of the training is self-awareness: ‘Self-awareness involves being conscious of one’s own world view, beliefs, values, and cultural biases acquired through enculturation to our native culture.’ He emphasizes that having a conscious knowledge of the assumptions of one’s own culture, its customs, values, and biases provides a framework for interacting with a new culture. It is most crucial for first-time missionaries to be disciplined in learning about their host’s new culture. Kietzman points out that first-term missionaries should direct their learning and adaptation, so that they will be accountable for their own learning. This requires self-motivation and a directed-learner’s attitude.[41] He suggests that trainees should focus their readings and reference work specifically on the country where they will serve. This includes researching comprehensive information about the target country and its culture, as well as the specific people group. I believe this suggestion needs to be considered for inclusion in general anthropological sessions of pre-field training programs, so that missionaries can spend more time and effort, even before arriving on the mission field, studying the assigned or targeted culture and people.

4. Minimizing Intergroup Conflicts

To resolve intergroup conflicts, a variety of strategies to remove sources of competition are needed, thus limiting their competitiveness or derogating their members, and avoiding or denying social comparisons between groups. The following suggestions are applicable for the process of initial training and during years of missionary service where missionaries live in the field among cross-cultural workers.

- Recognise that our cultures are biased; be open to recognise these biases.

- The need to study both the culture in which we minister and our own in order to compare and evaluate the two. For that reason, this study gave a good deal of space for that cultural aspect.

KS Lee, who has been working in the Philippines as a mission practitioner, suggests developing a new curriculum for pre-field missionary training. The following are some of his suggestions:[42]

- Set clear communication channels between the sending body and receiving body and provide clear job descriptions for the new missionaries;

- Learn how to handle meetings and agreements in the field through culturally- accepted etiquette and proper communication skills;

- Cross-cultural and customs studies: comparative study of her/his own culture and adaptive culture; and

- Analyse success/failure through field case studies.

5. Biblical Based understanding

Hiebert suggests an elucidation worth knowing by all Christians who are working with different cultures:

The dialogue between us and our national colleagues is important in building bridges of cultural understanding. It is also important in helping us develop a more culture-free understanding of God’s truth and moral standards as revealed in the Bible. Our colleagues can detect our cultural blind spots beter than we can, just as we often see their cultural prejudgments better than theirs. Dialogues with Christians from other cultures help keep us from the legalism of imposing foreign beliefs and norms on a society without taking into account its specific situations. It also helps keep us from a relativism that denies truth and reduces ethics to cultural norms.[43]

CONCLUSION

In the current ‘global village’ situation, daily cross-cultural activities are inevitably increasing and it is expedient to learn how to minimize conflicts and misunderstanding between different cultural groups and individuals. For this reason, a compelling priority is to increase the ability to understand and to respond well to conflicts for the survival, peace, and accomplishment of a common goal. Efforts, especially by intercultural program designers and trainers, can actually help trainees who wrestle with cross-cultural issues. I hope that cross-cultural organizations can take steps to plan programs in which both missionaries and nationals learn to cope with and adjust to their differences and move towards integration. The programs do not necessarily have to be formal ones, like large gatherings of denominational meetings, but rather they can also be small group interaction events such as sport events, potluck lunches, outings, and etc.

=========

Esther Lee Park

Dr. Esther Lee Park is currently an Associate Missionary serving with Glocal Leaders Institute, CA, USA as Director of Research and Development. Esther received her Ph.D. in Religious Studies in 2014 from University of Wales, United Kingdom.

======

ENDNOTES

[1] Everett Mendoza, Radical and Evangelical: Portrait of a Filipino Christian (Quezon City, Philippines: New Day, 1999), p. 9.

[2] Tuggy, p. 7. He describes it as “Philippines today may be called either the most Western of the Eastern countries or the most Eastern of the Western!”

[3] Neils Mulder, Filipino Images: Culture of the Public World (Quezon City, Philippines: New Day), p. 6, p. 182.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Bautista, VV (1988) “The Socio-Psychological Make-up of the Filipino”, In E Miranda-Feliciano (ed), All Things to All Men. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day, p. 9; Antonio Tujan Jr, ed, Transformative Education (Manila: Ibon, 2004, pp. 5–6, quoted in Glicerio Maniquis Manzano Jr, ‘Developing Appropriate Training Programs for Filipino Intercultural Ministry Workers’ (DMiss diss, Asia Graduate School of Theology, Philippines, 2008), p. 56.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Renato Constantino, A Past Revisited (Manila: Renato Constantino, 1975), np, quoted in Bautista, p. 10.

[8] Tujan, A (ed) (2004) Transformative Education. Manila: IBON. pp. 5–6, quoted in Manzano, p. 57.

[9] Teodoro Agoncillo, Filipino Nationalism 1872–1970 (Quezon City, Philippines: RP Garcia, 1974), quoted in Virgilio G Enriquez, From Colonial to Liberation Psychology: The Philippine Experience (Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Press, 1992), pp. 1–2. Historian Agoncillo claims the unique argument that the dominant home-grown religion is the Iglesia ni Kristo (consider it as a cult). He continues that even if Catholics comprise over 80% of the total population, the genuine Catholics probably do not comprise 0.5 % of the whole population, while those who belong to the Iglesia are devoted followers and loyal to their Church.

[10] Niels Mulder, Inside Philippine Society: Interpretations of Everyday Life (Quezon City, Philippines: New Day, 1997), p. 130, 133.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Enriquez, VG (1992) From Colonial to Liberation Psychology: The Philippine Experience. (Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Press, 1992), p. 2.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Mulder, Inside Philippine Society, p. 18.

[15] Ibid. p. 131.

[16] Rodney L Henry, The Filipino Spirit World: A Challenge to the Philippine Church (Manila: OMF, 1986), p. 11.

[17] Deborah Terry and Michael A Hogg, eds. Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Context: The Role of Norms and Group Membership (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2000), p. 97. The argument is “the social norms often produce public behavior that is inconsistent with individuals’ private attitudes. Social norms are properties of situations and groups, not of individuals. They develop thorough processes that have only an indirect and partial connection to the characteristics and views of those who are influenced by them. Therefore, the normative behavior that is exhibited in public settings is frequently counter-attitudinal for some or even most of the people who are enacting it.”

[18] Dadkhah Asghar, Susumu Harizuka, and Manas Mandal, ‘Patterns of Social Interaction in Societies of ASIA-Pacific Region’, The Journal of Social Psychology 139.6 (December 1999), p. 730. They argue that personal goals are subordinate to the goals of the group, particularly in collective societies. Moreover, the socio-centric (collective) nature of Asian culture like Philippine society suggests that interpersonal interaction regulates behavior patterns: self is defined as an aspect of a group.

[19] Jack Scarborough, The Origins of Cultural Differences and Their Impact on Management (Westport, CT: Quorum, 1998), p. 74.

[20] Ibid.

[21] George Paik. The History of Protestant Missions in Korea 1832–1910 (Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 1971), p. 25.

[22] Martha Huntley, Caring, Growing, Changing: A History of the Protestant Mission in Korea (New York: Friendship, 1941), p. 8. Huntley summarizes this Confucian world order, and the duties and attendant virtues of inferiors, clearly: Father and son — filial piety; Sovereign and people — loyalty; Husband and wife — deference; Older and younger brother — obedience; Friends — faithfulness.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Lewis R Lancaster, Richard K Payne, and Karen M Andrews, eds., Religion and Society in Contemporary Korea (Berkeley, CA: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, 1997), p. 49. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=9980815 [accessed 20 March, 2008].

[25] Jack Scarborough, The Origins of Cultural Differences and Their Impact on Management (Westport, CT: Quorum, 1998), p. 74.

[26] Theodore Gochenour, Considering Filipinos (Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural, 1990), pp. 7–8.

[27] Violeta V Bautista, ‘The Socio-Psychological Make-up of the Filipino’, In All Things to All Men, ed. Evelyn Miranda-Feliciano (Quezon City, Philippines: New Day, 1988), p. 1.

[28] Leonardo N Mercado, Elements of Filipino Philosophy (Tacloban City, Philippines: Divine Word University, 1976), p. 110.

[29] Landa F Jocano, Management by Culture (Metro Manila: Punlad, 1999), p. 8.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Landa F Jocano, Management by Culture (Metro Manila: Punlad, 1999), pp. 72–74 .

[32] Ibid.

[33] Paul G. Hiebert, Anthropological Insights for Missionaries (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1985), p. 34.

[34] Scarborough, p. 268.

[35] Paul Hiebert, “Cultural differences” In R Winter and SC Hawthorne (eds), Perspectives on the World Christian Movement. 3rd ed. Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, p. 378.

[36] Charles Kraft, Charles H Kraft, Anthropology for Christian Witness (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1996), pp. 32–33.

[37] Dale Kietzman, “Effective Cross-cultural Leadership Development”, In Timothy K Park (ed), New Global Partnership for World Mission (Pasadena, CA: IAM Institute for Asian Mission, 2004), p. 91.

[38] Ibid. p. 90.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] KS Lee, “Missionary Work in Partnership: A Case Study of the Korean Presbyterian Missions Working Together in the Presbyterian Church of the Philippines”. Unpublished Thesis (DMin), Fuller Theological Seminary,2004. p. 154.

[43]3] Hiebert, “Cultural Differences”, p. 380.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.