- April 1, 2019

- Posted by: admin

- Category: advance

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there have been various discussions among field practitioners and missionary theologians to define the missional significance of the diaspora phenomenon worldwide. The most significant of these were the academic conference for celebrating the centennial of the Edinburgh Mission conference in 1910, the Diaspora Division of the Third Lausanne World Evangelization Conference in 2010, and more recently the IAMS assembly in Toronto in 2012. In the meantime, Korean diaspora around the world has also held forums with diverse issues. Korean Diaspora Forum (KDF) was one of the significant forums among them.

This paper will address the study of the three facets of the diaspora phenomenon:

A brief overview of major mission theologies on the diaspora phenomenon that has emerged as an important feature of modern missions;

Major diaspora movements that have been conducted worldwide in response to the changing mission environment (especially focusing on Global Diaspora Network with the Lausanne Movement);

Korean diaspora missionary movements which briefly propose strategic missions in Central Asia, Russian-Korean, Chinese-Korean, and North Korean diaspora. These have not been included in the scope of research and interest for the modern era of the Korean diaspora.

WORLD DIASPORA PHENOMENON

Today, diaspora is becoming more and more a global phenomenon within the dynamism of globalization than ever before in human history. Jehu C. Hanciles, who was once a research professor at Fuller Theological Seminary, states that “important religions have strengthened their place in the past due to immigration and scattering, and Christianity is the most representative of them.” In short, the expansion of Christianity can be said to be a history with the Diaspora.

Since the ‘diaspora’ phenomenon emerged as a global mega-trend, both the evangelical and ecumenical parts are attempting to define it from a theological and missiological point of view. One of the champions is the Global Diaspora Network (GDN) together with The Lausanne movement. The GDN published a compendium of Diaspora Missiology in 2016 as a result of a five-year study with many practitioners, missiologists, and theologians. Apart from GDN, there were also various research papers and presentations related to ‘diaspora’ during the past decade all over the world. However, it will take more time to establish a robust theological framework for the diaspora mission mainly because of its diversity and complexity beyond our contemporary mission traditions.

THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON DIASPORA PHENOMENA

– Daniel Groody and Migration Theology

Groody focuses on migration issues in South America. According to him, there are three levels of migration theology. First, Pastoral level: to meet the needs of immigrants; Second, Spiritual level: what spiritual point does immigrants have about immigration?; Third, Theological level: This is a whole picture that combines the above two, and is regarded as a stage of the theological interpretation. Groody has four theological viewpoints: 1) Imago Dei must be restored equally to immigrants because all humans have the image of God. 2) The word of reconciliation through Verbum Dei, a unity as a body and forgiveness, must be made through immigration. 3) The ministry of the redemption of Jesus Christ, Missio Dei, must be achieved without discrimination to anyone. 4) Visions of God’s Kingdom, Visio Dei, must be realized without discrimination on the border.

In summary, he argues that immigration is no longer a social, economic, or political issue that governments are discussing, but a theological framework for human life and dignity.

– Peter C. Phan’s Views on Migration in the Early Church times of Fathers

A Vietnamese theologian Peter C. Phan, in his paper, articulated the immigration characteristics of the age of the Fathers in the early churches as follows: First, the early Church Christians experienced massive immigration. Second, this movement began in conjunction with the missionary activities of the church. Third, the reason for the movements was religious and political persecution, and at the same time, the movement was through trade, with the more important reason being the preaching of the gospel. Fourth, this movement occurred simultaneously with both internal and external movement. Fifth, as in other movements, it is a movement in the centre of the metropolis. Sixth, like the Jews, Christians formed a dynamic community through long-term settlement in the city. Seventh, unlike the Jews, they were treated as outsiders without any vested rights. Eighth, they quickly adapted to local cultures like other immigrants. Ninth, at the same time they have spaced certain distances from the surrounding societies, especially in religious practices. Tenth, the Christian Diaspora, is a pattern of movement in the population that has been repeated in history.

– Theological Framework of Enoch Wan’s ‘Diaspora’ Missiology and Joy Tira

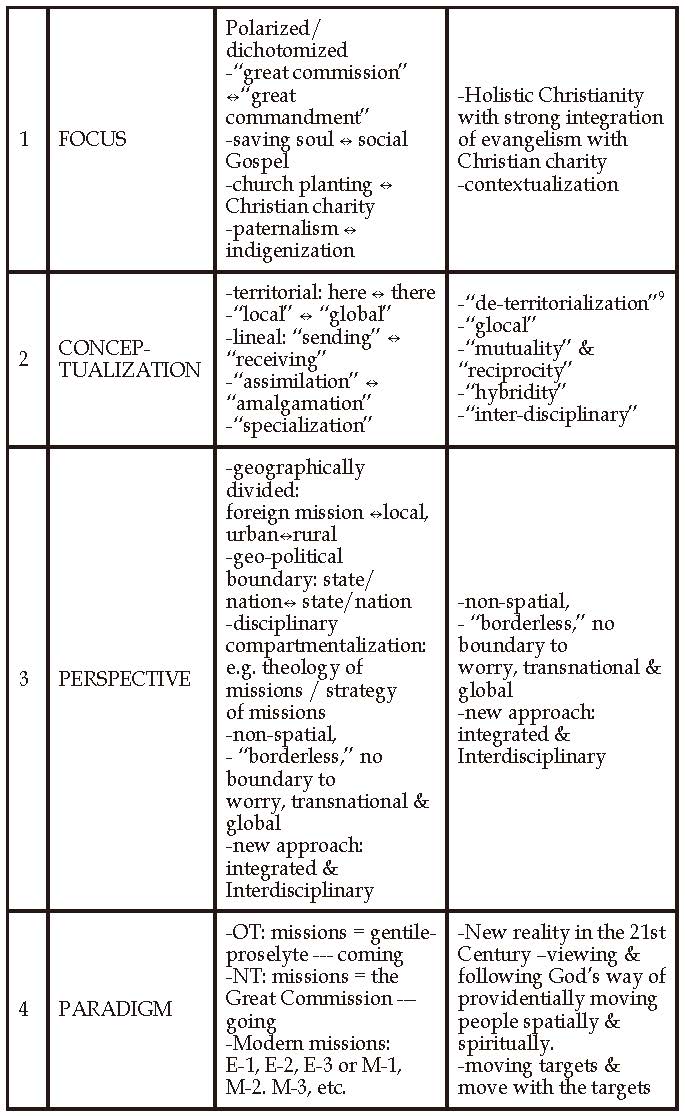

Enoch Wan defines ‘Diaspora Missiology’ as a systematic and academic study of the phenomenological approach on diaspora and of understanding the mission of God through theological review. For the diaspora phenomenon in the Old and New Testaments, he found patterns of scattering and gathering, and presented a series of examples in the Bible. The difference between traditional versus diaspora missiology is summarized as follows;

Comparison of traditional missiology and diaspora missiology

The methodology of the Diaspora missiology covers a range of cross-disciplines, and the major areas include cultural anthropology, demography, economics, geography, history, law, politics, and sociology. In addition to these areas of study, research topics such as migrant, immigrant, ethnic conflict, diaspora phenomenon research, globalization, urbanization, pluralism and multi-culturalism are necessary. As the diaspora phenomenon becomes more and more widely spread, the application of missiology of diaspora is prominent in our mission practice in order to discern the avenue of the missionary engagement in the future.

In order to support the framework of the missionary study by Wan on diaspora phenomenon above, Tira, in his paper, pointed that God’s sovereignty is at the centre of all diaspora phenomena and summarized the following themes as a significant part of the theological reflection for Diaspora.

1) God of the Trinity- God as Creator and human Saviour. He intervenes in the movement of human history (Acts 17: 26-27). He also gives human beings stewardship responsibility for all things and takes care of them through the freedom of residence. As a result of human depravity and expulsion by sin, the wandering of Cain, and the events of the Tower of Babel, “culture has developed and flowers of civilization have emerged … racial and ethnic gaps in modern society have become prominent.” However, the consequences of the act of God ultimately result in the completion of God’s plan (Rom 11).

The Incarnation of Jesus Christ is of great importance as a theological model of ‘Purpose Driven Immigration (Diaspora)’. Through His earthly life, He showed his disciples what life should be for the kingdom of God, and moreover not only understood the sufferings of the scattered, but gave them hope. The earthly command of Matthew 28 convinced the disciples that God’s kingdom would be extended beyond space and time.

The Holy Spirit as the Conductor of Mission who participated in the history of creation is involved in the formation of Israel and the creation of the Church, and ultimately plays a leading role in the plan of redemption of mankind. The Holy Spirit is present to the disciples scattered for the preaching of the gospel of the kingdom to fulfil the earthly mandate. (Matthew 28:20)

2) The Church’s identity and mission in Jesus Christ. The “mobility instinct” implied in Acts 1: 8 goes beyond all boundaries in conjunction with missionary purpose, and the universal church transcends the boundaries of local churches in all ages and spaces. Through prayer for the disciples of John 17: 11-21, we can realize that the scattering of the Church is the intent of Jesus.

3) The union of the scattered ones at the end (Eschatology)- The kingdom of God is present and all Christians are heavenly citizens, but in this land they live as witnesses as ‘pilgrims with purpose’. And at the end all the people scattered before the throne of the Lamb are gathered together (Rev 7: 9-10).

4) Cosmic conflict and spiritual warfare- When disciples were scattered for the preaching of the gospel, Jesus gave them the ability to overcome the power of darkness (Luke 9: 1-2). The apostle Paul says that all Christians participate in universal conflict and spiritual warfare. (Ephesians 6:12) Amongst immigrants, the abuse of women and children through human trafficking and the sex industry is a prime example of spiritual warfare. Christians in the diaspora situation are exposed to spiritual warfare, and for the expansion of the kingdom of God. We must firmly believe that the initiative of this war is with God, and at the same time we must bear all the training necessary for spiritual growth.

5) The Scripture as a mission manual- The Bible is the final authority manual for world mission. It includes progressive redemption, the history of the early church, the progress of the gospel, and the apostolic ministry so that the theology and missiological considerations of the phenomenon of the diaspora should be based on the Bible and its principles.

– Jehu Hanciles’s View on Africa’s ‘Diaspora’ History and Missionary Significance

In his article, Hanciles mentions about, the relationship between immigration and the expansion of religion. He further notes that the current form of immigration will have a profound impact on religious activities in the 21st century. Samuel Escobar also pointed that, “the migration model of today is an important flow of the Christian mission in the future, but has received little attention from the institutional missions.”

Hanciles examined closely the expansion of Christian mission during the era of Western imperialism and colonialism, and analysed that the flow of missions in the great wave of migration of large populations of European and non-Western labour forces in that period were carried out. These two events eventually led to the creation of a new order called global migration. In particular, colonialism established a transnational structure or interstate system to promote the era of global immigration and the disintegration of the Western imperialism in Europe caused a large scale of liberated manpower of non-Western countries to move to Europe. It was in the era of global immigration, what we call, ‘Post-colonialism’ from 1960s that the migration has been accelerated from non-Western to Western and South to North. As a result, various phenomena appear as follows.

1) Their movement goes with religion. Religion is a link to the place where they originally lived and is an important means of retaining their identity. Even if they are not religious from the beginning, they tend to pursue religious devotion to deal with isolation and loss of life.

2) Immigration also affects the countries that immigrants left. In the case of Africa, the loss of human resources causes a “brain drain” due to a third of skilled workers moving to Europe. As a result, international immigration is a result of the imbalance of economy also contributes to the immigration nation. From another perspective, immigrants are perceived as being a huge source of income for their home countries.

3) The pattern of international immigration that is taking place now is not to settle with a threat to life anywhere but a foreign country, but to recognize both countries as a place of life and to act as a bridge between them. The tendency of pattern is so-called “transnational migration.”

4) Modern immigration (diaspora) is “a network-driven phenomenon. At first, they move from the established contact point to the centre of the immigration.” Thus, unlike the Western linear structure,” non-western immigration forms are cellular organized and move along already established relationships in the society, lead to leadership and understand communication and human relationships in the context of the community that have been set up.”

5) The movement of the South-North created a link between the former colonies and the ruling countries, and many Christians of the former colonies migrated in this passage. For example, Africans who came in from the 1960s due to economic immigration and refugees have formed 3000 communities of faith in England alone. It estimates that the number of people across Europe is three million.

6) The growth of non-Western Christianity is promoting immigration. In particular, the members of the fast-growing African charismatic or New Pentecostal churches are the most mobile groups for ascendancy, and along with them, these churches have an international network, which tend to further promote immigration.

7) The nature of the South-North movement tends to pursue a New Testament model, in which church-centred, incarnate witnesses’ lives, and individual creativity, emphasis on spiritual power, house churches, self-supporting life style is pervaded.

– Summary of Key Elements for Diaspora / Immigrant Mission Theology

It is the sovereignty of God. Through the Book of Exodus and the Babylonian Exile, it is noticed that God himself draws the case with sovereignty and the intent for the redemption of human beings by scattering. Groody briefly described it as Imago Dei (restoration of image), Missio Dei (redemption ministry), and Visio Dei (vision of God’s kingdom). When we lose the identity of scattering, He puts us on the bridle of slavery and at the same time teaches us to restore the lives of witnesses, and eventually leads us from despair to hope. In this sense, God still exercises sovereignty through his “radical dislocation.”

It is the incarnation of Christ. Jesus Christ shows us the Diaspora identity most vividly. Through the Lord’s Supper, God first showed us the typical pattern of purposed driven migration. From the perspective of the world, immigration is viewed as a social, economic, and political issue, but in the context of the Eucharist, it is a theological problem that signifies a union of all humans without any conditions for the reconciliation with God.

Christian identity. Christians are essentially immigrants (paroikoi). They are ‘the third race’ in which they live in harmony with the world but not of the world with the kingdom mind. They have faith of eschatology with a desire for the spiritual things and the last union at the end of the world.

Immigration theology is cross-cultural, and counter-cultural character. Counter-culture, as clearly defined by Leslie Newbigin’s “Gospel & Our Culture Network” movement, means it does not deny secular culture, but rather criticize human culture, and give the initiative to the gospel in order to create a new culture.

The identity of the church. As some scholars have argued, the essential features of the Church are in the mobility instinct (Acts 1: 8) and migrantness. The theologian Phan saw that only immigrant churches with these features could obey Christ’s earthly orders and truly care for immigrants in the world with faith, hope, and love. A true church should be understood as a diasporic faith community standing in a prophetic tradition, not a religion (temple concept) based on tradition.

THE DIRECTION OF THE LAUSANNE DIASPORA MOVEMENT AND THE KOREAN DIASPORA MISSION

Recent data indicate that the Lausanne Diaspora movement originated in the Chinese Coordinating Committee for World Mission, which began in Hong Kong in 1976. It is also the fruit of the gathering of Chinese participants from ICCOWE held in Lausanne in 1974. After the Second Manila Lausanne Convention in 1989, the South Asian Concern was formed, and the following year, the North American Consultation of South Asian Christians (NACSAC) began.

Tom Houston, the then Chairman of the Manila Conference officially organized the Lausanne Diaspora Movement. And for the first time in 1998, the International Diaspora Leadership Conference was held in Edmonton, Canada. In 2004, the Lausanne Occasional Paper No. 2 ‘The New People Next Door’ came out at the Lausanne Forum in Pattaya. 55. This document was a breakthrough in evangelical mission thinking. At that time, the term ‘Scattered’ came out which summarized the Diaspora missions of Filipino regardless of Lausanne.

In 2007, Joy Tira was elected as a senior member of the Lausanne Diaspora and began to form members with other diasporas at the Lausanne Leadership Conference in Budapest, Hungary. At that time, I was commissioned to publish a booklet of the Korean Diaspora. For the publication of this booklet, in conjunction with the Korean Diaspora Forum (KDF) and the Korean Diaspora Mission Network (Kodimnet) for the past two years, the book of Korean Diaspora and Christian Mission was published with a thousand copies in October 2010. It was officially distributed to the delegation. The revised edition has been published by the Regnum Publishing House in Oxford and the Korean Diaspora Research Institute (KRID) in April, 2011 as a series of mission studies in Oxford Centre for Mission Studies(OCMS).

In 2009, the Lausanne Diaspora Leadership Team (LDLT) was formed in Manila where various diaspora ministers, theologians, missionaries, field workers, mission strategists, and others, tried to set up the theological foundation of Diaspora including at the Seoul Declaration on the Diaspora Missiology in Seoul at the end of 2009. In April 2010, a conference on European diaspora issues was held in Oxford, and the results were presented in the journal “Transformation of Oxford Centre for Mission Studies”.

At the 3rd Lausanne Evangelical Congress held in Cape Town, South Africa in October 2010, the topic of ‘Diaspora’ was one of dominant features. During the meeting, many topics dealt with specific issues in the mission field. But at that time, Diaspora was comprehended as an overarching phenomenon manifested in the 21st century mission. It was also a significant factor in solving the challenges of field missions and recognized that the Diaspora was already positioned as a new paradigm and direction of the new missions. This so-called ‘Divine Conspiracy’ on Diaspora-the mission through the Diaspora, is a God’s mission strategy specifically designed for long-standing Christian history.

As a natural consequence of this convention, in place of the LDLT which has been leading the Diaspora movement, Diaspora leaders from various countries gathered and created Global Diaspora Network(GDN) during the 3rd Lausanne Congress in 2010. Their aim has been to spread the Diaspora movement more globally and to establish an effective platform of solidarity with major evangelical movements around the world.

For the future of the Mission Movement after the 3rd Lausanne Congress with GDN, Enoch Wan, Joy Thira, Ted Yamamori, Hun Kim and other practitioners who have been leading the Lausanne Diaspora movement have been organizing an executive committee and held a Post-Cape Town meeting on February 20-21 in Paris. The meeting created a roadmap to prepare the Global Diaspora Forum, led by Global Diaspora Network with Lausanne movement in 2015 in Manila.

The network, which consists of two organizations: the International Board of Reference and the International Advisory Board, established the GDN office with the Philippine Security Exchange Commission in Manila, Philippines. The reason for this is that the global church is symbolically leading the movement.

The goal of the GDN is to consolidate with regional organizations and issue groups related to diaspora missions. Discovering and nurturing the next generation of leaders and achieving academic research related to Diaspora, with GDN being a trailblazer in the field of diaspora missions. Holding the Lausanne Global Diaspora Forum in Manila in March 2015, the aim is to produce the Compendium of Diaspora missiology in this forum with 500 field workers and scholars who understand the diaspora by region, ethnicity and country.

In relation to the Korean Research Institute for Diaspora(KRID) and the Korean Diaspora Networks (KDF, KODIMNET, KODIA-KWMA Diaspora Division), the GDN strives to find ways to cooperate with each other specifically. During the Korean-American Diaspora Forum conference in L.A. America, 2011, a partnership agreement has been made between GDN and KDN for promoting Diaspora cause.

The task of GDN with Lausanne movement now is to introduce the theology, missiology, and practices of the diaspora perspective and to disseminate them appropriately to seminaries, mission training groups, formal and non formal training programs. For this purpose, regional diaspora networks are being organized for each continent.

THE CASE OF KOREAN DIASPORA MISSION IN EURASIA: CONSIDERATIONS ON DIASPORA MISSION STRATEGY FOR CENTRAL ASIA

It is necessary to revisit the missionary importance of Korean Russian for the Central Asian mission strategy. Korean Russians are intended to be a new mission potential that God has providentially scattered for evangelizing Central Asia more than a century ago. They have been playing a role of an important guide for Korean missionaries especially when Protestant missions including Koreans surged the Soviet Union after its collapsed in 1991.

For Korean missions for Central Asia, it is necessary to have a new perspective by approaching the mission through Korean Russians. At present, there are not many papers published in Korea to study various strategic research about mission with Korean Russians in Central Asia. Now as the mission perspective is aimed at ‘holistic missions’ that consider both aspects of social salvation (demonstration of the Gospel) and a mere evangelism (proclamation of the Gospel), it is inevitable to have a symbiotic perspective on this area too with an interest in the cross-disciplinary domain of the diasporic point of view.

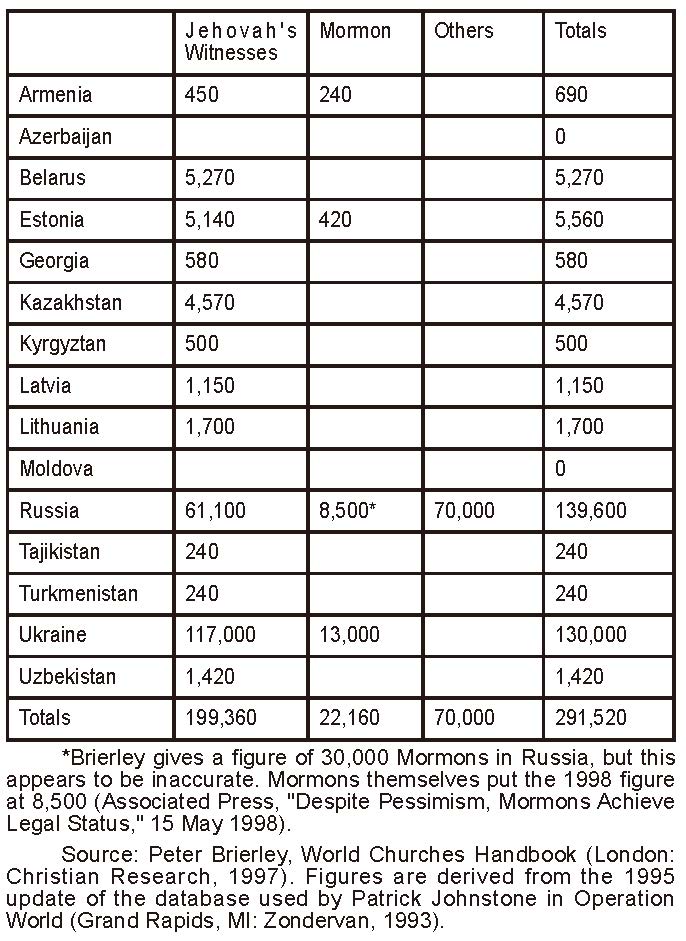

As I visited Ukraine in March 2012 and chatted with Korean missionaries in Kiev, I saw two facts from a diasporic standpoint. The first is that there are very few ministries for the 20,000 Koreans in Odessa and Crimea. Currently, there are about 120 Korean missionaries in Ukraine, who are ministering local and migrant Russians. But it is realized that a strategy that does not exclude the possibility of missionary work through those who are familiar with the local situations has to be developed. And around the world, Ukraine has exported its workforce (World Bank 2010) to Mexico, India, Russia and China, with a population of 6.5 million people (14% of the total population). In Russia, 4.4 million, 2.4 million in Kazakhstan, 150,000 in Uzbekistan, and 100,000 in Kyrgyzstan. Around the world, 14.7 million people (2004 statistics – Wikipedia) live the Diaspora life.

The missiological significance of this phenomenon requires us to change the present mission perspective more intentionally. For example, if they are to evangelize and serve the Koreans living in Ukraine, they would have a vision to evangelize 7 million Ukrainians too, along with Koreans living in the former Soviet Union. Furthermore, it is believed that appropriate strategic application to diaspora missiology are needed in order to develop the ministry associated with the Diaspora people scattered around the world from Central Asia. (For example, mission for 2.5 million Ukraine people in North America) This kind of ministry may be able to meet several times the role of Korean missionaries in terms of mission efficiency.

It seems that the efforts to utilize the Korean-Chinese Diaspora reserved for Central Asia, China, and North Korea missions are more urgent than ever. The history of the Korean-Chinese Diaspora developed in various ways. The two major periods are divided into two periods: first, from the Korean peninsula to the northeast of China; second, from the northeast of China to the Korean Peninsula and the entire world; The first wave of migration in the late 19th century occurred when people migrated to the province of Jilin province today. The second wave of migration came to the Jilin province in the 1910s by independents and some farmers. In the 1920s and 1940s, the third migration was carried out by the Gyeongsang Peasants in the Heilongjiang Province and the Liaoning Province in accordance with the forced migration policy of Japan. In the 1950s and after the 1960s, the 4th Korean group of immigrants moved to North Korea to avoid the Chinese Cultural Revolution and famine. Since the 1980s to the present, the 5th Chinese immigration has moved to Korea since the Chinese reform and the opening of the Korea – China diplomatic ties. The 6th Movement has migrated from 1990 to present time to other western countries such as Japan, USA, and Australia. Since the 1990s, the 7th group of Chinese immigrants had moved to the Chinese coastal area and the inland metropolitan area.

As shown in the above history, since the 1980s, the Korean-Chinese Diaspora has been dynamically developed in line with the Chinese opening policy, and everywhere I can see Korean-Chinese churches established and working closely with Korean missionaries. In recent years, they have moved to Europe and established churches in the centre of the Korean ethnics in London, with a Korean-Chinese minister recently being ordained and working for a German congregation in Germany. It is more important than ever that the evangelization and the mission strategy for the Korean-Chinese diasporas around the world are implemented, with 1.83 million Chinese in China and 500,000 in Korea. Rev. Hae Hong, who is the pastor of Korean-Chinese church, writes in his book, “Diaspora Korean-Chinese”, mentioned that “If the Christian culture is strongly settled to 500,000 Korean-Chinese people in Korea, then the power will reach 2 million Korean people and mission in China… It is expected that it will cause a huge wave of immigration in China. For the future of China, we should also positively look at the role of the Korean-Chinese in the middle.” In addition, Seung-ji Kwak, a team leader of Yeunhap News agency in Korea, recognized that their role in rebuilding North Korea after the reunification was absolutely vital, saying, “Korean-Chinese are the key unification forces most closely related to the reunification of the Korean peninsula, It is a preliminary task for them to actively participate in the unification discourse.” Moreover, unlike Koreans, the Korean-Chinese people have a slight sense of tension with North Korea and North Koreans. In addition, the Korean-Chinese have little administrative constraints on accessing North Korea, and have language (including dialects) and culture homogeneity. In fact, Korean-Chinese people are frequently visiting Pyongyang, N. Korea or the Rajinsunbong area, and they often make contact with North Koreans and officials through business activities. Given these points, it is anticipated that the Korean-Chinese will be able to play an active and efficient role in all areas of society including the gospel at the stage of change, openness or unification of North Korea.

Although the link between Korean-Chinese and Korean-Russians in Central Asia should be pursued with a long-term perspective, it is expected that the next generation of the region will be able to cooperate through education in Korea and China Yanbian University. There are opinions that the role of the Korean-Chinese church is very important in rebuilding the church after the unification of North Korea. According to the leaders of Chinese Church in Yanbian and Beijing, they are currently free to travel to North Korea several times a year for short-term missions and to establish a framework for North Korean missions. When North Korea is opened, Korean-Chinese churches hope to help North Korean churches preferentially. The reason for this is that there is a concern that the confusion of Protestant mission that occurred after the collapse of the Soviet Union might be reproduced. After the opening of the Soviet Union, the infiltration of heresy is so severe that the truth of the gospel is distorted.

On the other hand, the identity problem of the Korean-Chinese diaspora is becoming an important issue from a sociological point of view. According to an observation by an anonymous minister, “It is important to plant the identity and historical consciousness of the Korean-Chinese people like the Korean-Russians, which is crucial to the holistic mission and the mobilization of the mission. The concept of roots and historicity is too weak, so that the individual’s direction of life is weakened, so they are lack of knowledge in Korean history and world history, and surprisingly ignorant in Chinese history. They do not put any value on Christian worldview of God’s intervention in history, as well as the value of money and success, but become extremely temporal, and with instant, low-level view of life. In addition to the harmful effects of communism, Chinese manoeuvrings of the nation’s absorption of the people has made a brilliant contribution to the racialization of ethnic minorities in China, including the Korean people. I think it is a crucial consideration to evangelization and missions education.”

A global mission network for the missionary mobilization of Korean Diaspora is in need for linking Korean-Russian and Korean-Chinese in Central Asia including North Korean refugees. Currently, there are more than 7 million Korean diasporas scattered in 170 countries around the world, and about 5,000 Korean churches are seen as the bridgeheads of missions. Until now, large and small Korean churches, mission councils and diaspora nets have now been organized mainly in North America, South America, Europe, Asia, South Africa and Australia, with efforts being made for regional unity and cooperation. In particular, the two organizations that I have been working closely with are the Korean Diaspora Missions Network (KODIMNET) and the Korean Diaspora Forum (KDF). In addition, the Korean Diaspora Network(KDN), proposed and formed recently by the Korean Diaspora Forum is advocating the Diaspora cause world widely. Koreans in Central Asia and China should also be encouraged to engage in the mission movement as a part of Korean Diaspora work force.

CONCLUSION

Now the world has become “from everywhere to everyone”, the recognition is that my place is a mission field at the doorstep is stronger than ever. In this age, no one can deny that the historical movement of humans is like an infinite tsunami. This phenomenon is calling for a strong “change” in the existing Christian mission. The Diaspora mission must seek new breakthroughs as God’s ultimate “Divine Conspiracy” for the salvation of all nations.

This new breakthrough will not be possible in the way of transplanting a better program following the practices that have been done so far, and in essence we have to worry about what mission is. As mentioned above, the intrinsic thing is to recognize God’s sovereignty that deliberately dispersed man (Acts 17: 26-27), reflection on the meaning of Christ’s incarnation, awareness of Christian’s identity as paroikoi (immigrant- 1 Peter 1: 1) and finally, restoration to the essence of church as mission. In order to restore to this essence, we must live a life practicing true biblical evangelical ecumenism following the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

The Central Asia ministry is no longer a regionally isolated ministry. Numerous tribes of this land are moving to every corner of the earth today (eg. Ukrainian), and the Korean-Russian, which God has hidden, is expected to play an important role in the future of evangelization. The Korean Church, which has established the bridgehead of mission through the Korean Diaspora Church in the world in the past, and has been working with the Korean missionaries in Central Asia, will be a leading partner alongside the other global churches at the front line of the gospel.

REFERENCES

Brierley, P., World Churches Handbook, London: Christian Research, 1997.

Escobar, S., A time for Mission, Leicester, Inter-Varsity Press, 2003.

Groody, D. & Campese, G. (eds.), A Promised Land, A Perilous Journey-Theological Perspectives on Migration, Notre Dame Indiana, University of Notre Dame, 2008.

Hanciles, J., Migration and Mission: The Religious Significance of the North-South Divide, in Mission in the 21st Century, Andrew Walla & Cathy Ross (eds.), Darton, Longman and Todd, 2008.

Kim, Sung-Hun & Ma, Wonsuk, (eds.) Korean Diaspora and Christian Mission, Oxford, Regnum 2011.

Phan, Peter C., Migration in the Patristic Era, History and Theology, in A Promised Land, A Perilous Journey, Notre Dame Indiana, University of Notre Dame, 2008.

Roswith Gerloff, “The African Christian Diaspora in Europe, Pentecostalism, and the Challenge to Mission and Ecumenical Relations” (Paper presented at the Society for Pentecostal Studies, Thirty first Annual Meeting, Lakeland, Fla. , March 14-16 2002).

Wan, Enoch & Tira, Joy (eds.), Diaspora Missiology, Missions Practice in the 21st Century, Diaspora Series No. 1, Pasadena, California, WCIU Press, 2009.

Kim, Sung-Hun, ‘Theological Discussion on the Phenomenon of Diaspora’, Journal of Frontier Missions (KJFM), Vol. vol.27 2010 3.4.

Hong, H., Diaspora Korean-Chinese, Seoul, Qumran Publishing House, 2012.

J. Hun Kim

azerikim@hotmail.com

Dr. J. Hun Kim is a reflective practitioner and studied as a researcher on the mission and Diaspora/migration with OCMS and Oxford. He was a Bible translator with Wycliffe Translators and published the Azeri Bible in Iran in 2013. He also served as Diaspora Consultant in Europe, served as vice-chair of Global Diaspora Network with Lausanne Movement. Now he is serving as a Coordinator of Equip7: Learning Community in Europe, helping refugee and Diaspora leaders better equipped for their own ministries. Recently he published “Korean Diaspora and Christian Mission” in 2011 which is endorsed by The 3rd Laussane Congress in Cape Town.

1 Comment

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

My brother, long time. Thank you for your paper. It seems that you have overlooked the most significant gathering on diaspora missiology ever organized under the Lausanne banner. The Global Diaspora Forum in Manila in 2015 was quite important and historic. Warmly, Cody