- July 13, 2019

- Posted by: admin

- Category: advance

CULTURAL ORIENTATION IN MANAGEMENT

Culture can be defined in many ways. One way, as Brislin elucidates, can be explained as ‘an identifiable group with shared beliefs and experiences, feelings of worth and value attached to those experiences, and a shared interest in a common historical background.’

In working cross-culturally, it is evident that people who were raised in two different worlds quickly become judgmental toward those from the other culture: missionaries and nationals. Moreover, management practices in an office can become problematic since two groups of people follow different work ethics and hold a different general world view. Schneider and Barsoux point out the misleading belief in the convergence of management practice that many managers and management scholars still believe, “management is management (consisting of a set of principles and techniques), and is considered to be similar to engineering or science.” They argue that despite technological and economic forces for integration or convergence in multicultural companies, there are great forces for fragmentation, one of them being culture. Along the same lines, Filipino anthropologist Jocano emphasizes the art of Management by Cultural awareness (MBC), stating in his cultural management book: ‘foreign and western-trained and educated Filipino managers should consider their employees’ culture more. In the office, the tasks may be technical in nature, but motivating people to peak performance is cultural.’ I think that comment also can be applied to missionaries who work mainly in cross-cultural settings. He goes on to say that MBC is the new key to achieving teamwork and cooperation:

…foreign techniques may be academically attractive, but they are seldom suited to the Filipino cultural temperament; effective management is the function of fit or match in the perceptions and expectations managers and workers have of each other.

CULTURE STUDIES

Philippines: It seems complicated to find a unified culture or personhood in the Philippine archipelago, a country of more than 7,100 islands and 45 vigorous languages. It is also challenging to define who “Filipinos” are, ranging from indigenous peoples living in ancestral domains to the more westernized inhabitants in the metropolitan cities. Thus, this paper will focus mainly on Luzon island, the Tagalog-speaking region, where I mainly engaged with the people.

Filipinos: According to the Filipino historian Constantino, the first to be called Filipinos were the “Españoles-Filipinos” or creoles, Spaniards born in the Philippines. Therefore, “Filipino”, according to Mendoza, is “fundamentally a political rather than a racial term.” Every phase of Filipino life has been influenced involuntarily by occupation and annexation for more than three centuries 1565-1898 by Spain, and for nearly five decades 1898-1946 by the United States. To all outward appearances, Filipinos seem to be the most Americanized and the most devoted Catholic Asians. However, church historian Tuggy tries to illustrate the complexity of Filipinos and their culture metaphorically as an onion:

Over it, all is a thin skin of Americanization…but peel off the layer of the onion, and you will see a heavily Hispanicized cultured Church and plaza. Fervent religious processions…but peel away this Spanish layer, and you will reach the Malayan cores. The Philippines’ dominant racial strain is definitely Malayan. The Philippines’ bilateral, extended family system is similar to that of other Malayan peoples of Southeast Asia. The Philippines’ underlying belief system, involving spirits and the anting-anting ‘charms’ also traces back to the Malayan core.

Philosophy and World Views

Concept of Equilibrium-maintenance (pagkakapantay-pantay, di pagkakatalo): Mercado employs the phrase “pagkakapantay-pantay,di pagkakatalo” (equilibrium-maintenance) as the Filipino concept of being in harmony with nature. They calmly accept the continuation of natural catastrophes such as storms, floods, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions and learn how to adapt in this harsh environment. Therefore, if this balance is disturbed, the Filipino expects suffering and other forms of misfortune. This way of equilibrium-maintenance with nature also applies to everyday life and interpersonal relationships. Well-known Filipino communication skills such as avoiding conflict, smooth interpersonal relationships (SIR), and group consensus are ways of coping with the disruption of peace and accepting pre-ordained destiny.

Centripetal Morality: ‘Centripetal Morality’ as explained by Timbreza is “people using the self (pagkatao) as the center, basis, or gauge of moral judgments, of good and evil.” It means that Filipino ethics depend on personal judgment and a self-oriented approach to morality. Timbreza notes that the basis of Filipino centripetal morality revolves around 1) the golden rule, and 2) the nonjudgmental or noncritical. The golden injunction is “what is bad to you; you should not do to your fellow man (ay huwag mong gawin sa kapwa mo).” The other noncritical morality is self-reflection and self-analysis through other’s weaknesses and faults that other people’s badness and goodness should be mirrored in and through one’s own personality. Sometimes this view of loose morality perspective confuses foreigners who were raised and taught to condemn misdemeanors and wrongdoing.

Value of Diplomacy: In Tagalog, “mas malakas ang bulong kaysa sigaw (a whisper is louder than a shout)” or “kapag ikaw ay magparaan, ay pararaanin ka naman (if you give way to others, you will be given way, too)” give a clue that diplomacy is the give-and-take to a problem or conflict between two parties, and in the process, a soft and congenial approach rather than a confrontational one is more reasonable and persuasive. In the same way, the “paupo (sitting position) “approach is preferred to the “patayo (standing position)” approach. A sitting position refers to peace talks at the negotiation table, while a standing position represents aggressive, combative, and disputative ways. Filipinos prefer indirect communication to avoid any confrontation. This indirect approach not only belongs to verbal communication but also when communicating emotions through pakikiramdam (a nonverbal way of receiving and decoding information). If a Filipino has hinanakit (hurt feelings) towards someone, it is not likely that he/she will tell the person directly; instead he/she will show his/her disapproval in a nonverbal manner, such as averting eye contact or more pointedly refusing to be drawn to any conversation by the erring party. The Filipino response is to catch the signals and to offer an acceptable pahiwatig (a nonverbal way of sending information) to appease the aggrieved party.

Filipino Family Structure-bilateral: To Filipinos, the family is the core unit of the Filipino kinship system. Understanding the Filipino kinship structure of extended bilateral family structure is central to the understanding of Filipino behavior; it represents the fundamental role of Filipino society.

The Filipino family rears children with equal attention regardless of their gender. Filipino daughters, for example, are treated equally in receiving an inheritance from their parents. Moreover, Filipino society embraces a bilateral family structure, with equal attention given to both the mother’s and the father’s sides of the family. Filipino bilateral structure is unique in that this association through kinship ties is a matter of choice by the individual or family. It means a Filipino family (or individual) can choose to continue close ties with either the mother’s or father’s side or both. Functionally, the symmetrical recognition of kinship on both sides of parents brings about equal distribution of rights, obligations, and privileges among a great number of fellow kin. Support and protection are given in time of need. In turn, the individual is also obligated to come to their kin’s side when they need his/her assistance, and declining to do so is considered a grave social offense. Reciprocity of family and kinship desire is a widespread phenomenon among collective societies.

Among Filipinos, child-rearing is always personal and emotional: the baby is rocked to sleep in romantic songs, and the child is never left alone. Jocano claims that a consequence of growing up in this sentimental environment is the patterning of sensitivity as an aspect of individual personality. The feeling of happiness with families is more valuable than a career to a typical Filipino. Tomas Andres attributes this to their roots, the Malay’s nature:

The Malay is the world’s baby of nature because nature has always been bountiful to him. His love for the fiesta is exorbitant. What matters are ‘the lovely here-and-now’…unemployment is not a social problem for him because most of the unemployment is by choice.

Filipino Kinship and Social Structure: One of the most potent elements of Filipino social structure is based on kinship. This kinship expands to ritual kinship, so-called compadre, and the parents’ relationship with ninong and ninang (godparents). Traditionally, godparents have the responsibility of functioning as second parents to their godchild. This Catholic practice beginning during infant baptism is still one of the essential rituals in Filipino life, not only among Catholics but also among Protestant Christians. Nowadays, these significant responsibilities have lessened, but there are underlining expectations of help in the upbringing and education of the godchild. This Filipino cultural themes of reciprocity are practiced from infant stage, primarily through the infant baptismal event, to adulthood.

Filipino Cultural Themes: Cultural particularities of Filipinos are reciprocity, collectivity, and sensitivity. Reciprocity is one of the by-products of early socialization as an infant in Filipino culture. Living in the social world of relatives, the Filipino child is enjoined by his/her older relatives to extend assistance to his/her fellow kin. His/her fellow kin are expected to return the favor. To a Filipino, the practice of reciprocity is not limited to his/her kinship boundary. In urban settings, the barkada (peer group/gang) serve as surrogate kindred, that is, this collective exercises the reciprocity of mutual assistance instead of kin, as in more rural settings.

Core Values-“Pakikisama (getting along)” and “utang na loob (debt of volition)”: There are two historic core Filipino values that are highly regarded: pakikisama and utang na loob. Pakikisama “getting along” is the norm for relationships within the society and the group, and it is rooted in the intrinsic Filipino value of pakikipagkapwa-tao “acts of helping, sharing and cooperating with others.” However, due to the emphasis on unity and peace within a group, a person’s individuality to some extent becomes merged with those of others. Utang na loob “debt of volition” is immeasurable and eternal, favor is given in return for past favor. The word utang refers to a “debt or an unpaid account.” Miranda explains this utang na loob as “a debt that has been interiorized as debt’ and the expected terms of repayment.” Miranda-Feliciano explains the effects of this core value as ‘to a Filipino, to show a lack of due gratitude is outrageous; being grateful is almost second nature to him. His sense of utang na loob defines his integrity as a person in the context of social relationship.’ However, this lifetime obligation to debts of gratitude is also a method of robust social control. It can be manipulated. For example, someone who is out to win indebtedness from others to serve his selfish interests can arrange situations and events to make himself appear agreeable and benevolent. However, this kind of networking can also be advantageous in many ways: once established, it enhances the group member’s social prestige and acceptance in the community.

Filipino Psyche

Filipino Kapwa (fellow human being): The Filipino core value of kapwa “fellow human being” is the necessary level of human relationships. The Filipino notion of “others” is not an opposite of “self,” rather it implies inclusively “self” and “others” as unity, a recognition of shared identity. The concept of kapwa is the starting point of all levels of interaction that are deeply rooted in respect for the whole of humanity.

Pakikipag-kapwa (shared identity): According to a Filipino psychologist, the central core value, pakikipag-kapwa “shared identity” is based on two presuppositions: 1) one treats another as his equal, irrespective of the person’s background; 2) one views relationships as momentous and demands that he attends to all rules of propriety as a clear sign of his providential will. Therefore, Filipinos are people-oriented; they avoid conflict and go along with a group’s or family’s decision rather than personal preference. However, the tendency to be loyal only to their family, friends, and associates, often results in regionalism, cliquishness, and exclusivity. This tendency of in-group favoritism can produce the following aspects of exclusivity: maka-angkan “extreme family-centredness,” tayo-tayo “we-exclusive,” atin-atin “ours-exclusive,” and kanya-kanya “self-serving attitude,”and kama-kamag-anak “family-exclusive”.

Pakikiramdam (shared inner perception): As kapwa is the foundational value among other value systems, pakikiramdam “feeling for another” is the pivotal value of shared inner perception. According to Enriquez, the father of Pilipino Psychology, Filipino values are classified into four major categories, consisting of 1)surface value, 2) a pivot, 3) a core, and 4) a foundation of human values. The surface level is an accommodative social value such as hiya, utang na loob, and pakikisama. The pivot interpersonal value, pakiramdam “shared inner perception,” is the internality-externality dimension in kapwa psychology. The core of the value system is the kapwa psychology that is explained as an extended sense of identity. The socio-political elements and foundation such as kalayaan “freedom,” karangalan “dignity,” and katarungan “justice” are constituted concepts of social justice.

Cultural Hybrids: Andres calls the Filipino philosophy of values as “hybrids” because cultural traits have been borrowed from the Arabian, Chinese, Indo-Chinese, Hindu, Indonesian, Spanish Catholic, and American Protestant, and combined to result in what is distinct “Filipino.”

As some Filipino scholars mentioned earlier, the Philippines, both as a people and a country, suffered from a long period of colonization. However, Filipinos’ high adaptability produced originality from some ideas borrowed from the colonizers. For instance, Spaniards introduced compadrazgo ‘god-parenthood’ Catholic ritualistic practice; Filipinos however, have used that practice as a compadrazgo system, a technique for alliance making. Through the baptism of a child, a relationship is set up between the child’s biological parents and (possibly nonrelated) persons who become spiritual parents. Through this system, the biological parents supplement social parents in order to give the child a social existence with economic and political significance.

The colonial process promoted a sense of inferiority among the colonized. Renato Constantino, a Filipino nationalist, claims that during the colonial era, the consciousness that developed among the people was that of captives, shaped and tailored to the need of the colonizers. He notes both Spanish and American influences in this way:

The Spanish friars saw to it that the natives, through religious conversion, became docile and illiterate, obedient and fanatical. The Americans, on the other hand, by using education with English as the medium of instruction, saw to it that the natives developed Western preference, thereby imbibing a Western consumerist orientation.

Gripaldo elucidates that the Spanish colonial government used religion as the instrument of domination. Before the educational reform of 1863, the friars did not teach the Spanish language to the natives; therefore, the net result was a colonial consciousness that was mostly ignorant, illiterate, subservient, and servile.

The arrival of Americans in the Philippines created confusion among Filipinos. Apilado comments on the abysmal situation like this: ‘the revolutionary fighters thought Americans would help them gain freedom and independence…instead they faced a new, more powerful and equipped colonizer.’ He also criticizes the colonial policy, where Americans welcomed nationals as patriots who collaborated with them, thus “purchasing loyalty,” which goes some way to explaining the present-day corruption. Therefore, some scholars have suggested some decolonization processes to regain their initial cultural values while other critics have harshly judged these values as causes of present-day ills in the society and the moral breakdown of institutions. For example, one of the prominent scholars, Jocano, expresses the former opinion in his book, Filipino Value System. He asserts that since Filipino traditional ways were viewed negatively, it caused confusion and produced incongruities in both society and culture, so Filipinos should cherish their own culture that the colonizers once distorted and devalued. However, the Filipinos’ psychological orientation lies somewhere along a continuum between the prototypical Asian values like humility, harmony, and modesty, and the Western values like individual worth, self-determinism, and nonconformity.

Filipinos’ Collective Identities: Most Filipino values appear to idealize group identity more than they emphasize personal independence. Belonging to a group is an ideal most Filipinos believe in and value dearly. A Filipino who is individualistic and too independent is most likely perceived as an unlikable fellow walang pakikisama “anti-social.” The Filipino word pakikisama “one for all, all for one” is an apt term for helping hands and seeking harmony with others. It is also a euphemism for whatever is best for the group to maintain smooth interpersonal relationships (SIR) with others, and for learning to subject one’s desires to the group’s approval.

Filipino Socialization: Ibang tao (outsider and hindi ibang tao (insider): The distinction between ibang tao “outsider” and hindi ibang tao “one of us” reflects the level of the relationship built and defines membership in a group that determines the boundaries or the extent of proper behavior for a person. In Filipino socialization, one is immediately “placed” into one of these two categories: in-group or out-group.

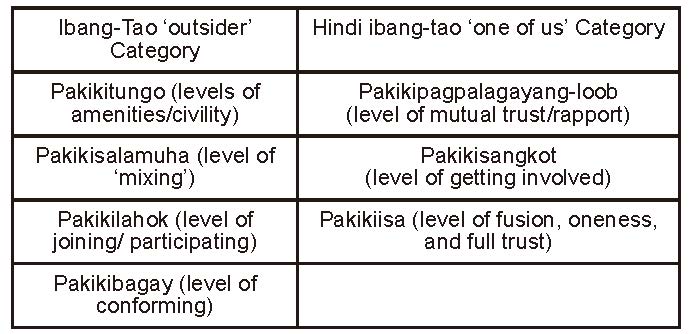

Social interaction is highly valued in Filipino daily life, and it can be seen mysteriously to foreigners. Pe-Pua sub-categorises five ways of social interaction within ibang tao “outsider”: 1) the most shallow level of interaction is pakikitungo “transaction/civility with”, 2) the next level of interaction is pakikisalamuha “interaction with”, 3) the more friendly interaction is pakikilahok “joining/participating”, 4) the level of building relationships is pakikibagay “in conformity with/in accord with”, and 5) pakikisama “getting along with”. On the other hand, if one is recognized as hindi ibang tao “one of us,” the relationship has reached the higher levels of pakikipagpalagayang-loob “being in rapport/understanding,” pakikisangkot “getting involved,” or the highest level of pakikiisa “being one with.” The following chart will summarise Santiago and Enriquez’s eight behavior levels previously stated in two different categories where Filipinos are identified:

Table 1. In-group and out-group categories in the Filipino context

Pakikisama (level of adjusting): As table 1 shows, the Filipino way of relationship development takes steps like building blocks: from pakikitungo , to pakikiisa “oneness.” However, unlike other cultures, the Filipino’s kapwa psychology takes a very flexible manner in drawing the line between “in-group” and “out-group” distinctions. Psychologist Enriquez explains the more in-depth and profound meaning of pakikipagkapwa “shared-identity” and its implication this way:

…it also means accepting and dealing with other person as an equal. The company president and the office clerk may not have an equivalent, role, status, or income but the Filipino way demands and implements the idea that they treat one another as fellow human beings (kapwa-tao). This means regard for the dignity and being of others.

For example, this Filipino core value of inclusiveness becomes problematic against the universal standard in an international organization. My observation goes back to the seminary full-time faculty annual planning retreat in the early days that was strictly for full-time faculty members only before the academic year starts. In later years, its invitation has extended to all staff and workers for a fellowship event. Thus, it became a predominantly Filipino fellowship activity alone since foreign faculty members have stopped attending this important yearly planning event.

Personalism: The Filipino cultivates a highly developed personal network not only within his/her kinship but also beyond. He/she is expected to exchange a wide range of services and resources among members. Raul Pertierra depicts the social network technique as:

Philippine society is based on the form of personal and collective prowess ensuring protection for allies, friends or kin and marked by a predatory orientation towards unto others. Strangers are fair prey and are converted into consociates, often through a mechanism of obligatory hospitality. Foreigners are often puzzled and charmed by such expression of hospitality, a rarity in the West until they realize that these represent attempts at incorporation into the personal network. While such displays of hospitality may be strategic, they are not necessarily duplicitous but simply ways of transforming a stranger into a consociate.

For instance, for the Filipinos a professor in the university is not only regarded as a teacher, but also as a fatherly figure; a classmate is not a mere fellow learner but at least a friend and at best a brother or sister.

The understanding of the Filipino’s private and public orientation is rather jumbled up. Pertierra writes, ‘Filipinos personalize the public sphere, and when possible, use its resources to pursue private gain.’ However, it may be not intentional or selfishly motivated, but it is expected that true leaders redistribute the gains among their followers. This redistribution issue sometimes causes conflict among different nationalities within denominations and international organizations.

SOME CULTURAL ISSUES

It comes from the Filipino sensitivity that a person’s feelings should not be hurt. The way of not hurting the other’s feelings can be explained with two essential elements: pakitang-tao “for appearance’s sake,” paramdaman “hint,” or pakikiramdam “being sensitive.” According to Lapiz, pakitang-tao is superficial cordiality to conceal from those not involved in whatever unpleasantness may exist between parties. Often, this superficial cordiality, never says “no,” causes misunderstanding as assent; especially in the case of evangelism by foreigners. In my experience with Korean short- term mission groups, I often felt evangelism reports were exaggerated with conversion numbers since everyone said “yes” to the foreign evangelists, especially to who brought gifts and goods.

Also, this courtesy stretches beyond the foreigner’s capacity to understand why an offender can neither be confronted nor corrected. This matter probably has been the most frequent cause of clashes between expatriates and nationals. Foreigners expect apologies when nationals make mistakes but seldom do nationals say “sorry” or admit wrongdoing in this context. The practice of superficial kindness or courtesy is to save everyone’s face, including the wrongdoer’s.

Another element is the culture of paramdaman “hint.” It means that you can insinuate to the other party that you may not be agreeable; nicely if possible. It seems that it requires indefinable sensations for those from different cultural backgrounds. This gesture is not only applicable to public civility but also any level of relationship.

Giving priority to the cultural practice of SIR (Smooth Interpersonal Relationship) and group consensus often creates a negative impression to foreign partners and is mistaken for lack of leadership or concealed dishonesty.

As it has discussed, peoples are clothed with their own culture, inside (values and world views) and outside (behaviors and customs). It is not an easy task to work spontaneously with people from different cultural backgrounds. Culture is learned and shared with others; it is not individualistic, but a consensus that regulates the behavior of its members. However, missionaries cannot effectively do what they seek to accomplish if they are ignorant of the cultural dimensions of the society in which they minister. By contrast, any lack of seriousness and too much concern for domestic matters from national co-workers often create conflict with missionaries who have perceived the situation and responded in their own culturally conditioned ways. Knowing Filipinos well and using their culture properly can spark nationals to a deeper level of loyalty and passion.

=========================

Esther Lee Park

eparkpts@gmail.com

Dr. Esther Lee Park served as a missionary in the Philippines for 15 years and currently back to the US and is serving as the Director of B.TH. English track at Presbyterian Theological Seminary in America, CA USA and Director of R & D at Glocal Leaders Institute, CA, USA. She received her Ph.D. in Religious Studies from the University of Wales, Trinity Saint David, UK.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.